We will be featuring the writings of members of the Celtic Buddhist Community. Included will be excerpts from an unpublished book completed in 2016.

An Introduction to Buddha Maitreya

by Bill Burns

This writing is about an issue or a reality that I have been wrestling with for many years. How to introduce a teaching or a teacher to the public without any attendant fanaticism? How to sensitively share with others something we deem valuable in our lives and development as human beings, minus the evangelical overtones. It turns out to be a difficult feat to accomplish. I think apprehension enters into it, not wanting to disturb or coerce or convince another.

We can’t necessarily find everything, every truth on our own. It would take an enormous amount of time, which is why we have teachers and guides. Transmission is important. It is why we need dharma teachers. We could wander on the wrong path for lifetimes without the luck of being redirected onto an aspirational arc. There is a journey to the healing of wrong views.

I believe anyone reading these words has had great good fortune. I, too, have had fortunate circumstances in my life. “Auspicious coincidence” was a term used by Trungpa Rinpoche when I received refuge vows in a ceremony with other sangha members in Boulder, Colorado in the winter of 1974. It was also auspicious when I was hired in 1965 as a camp counselor by the directors, John Perks and his wife at the time, Naomi. John and I would later connect in Vermont, again by coincidence. John has always had the vision of Celtic Buddhism, first and foremost, and around 2000 that began to manifest. My wife, Peg, and I began to take part in it. John became my root teacher, introducing me first-hand to the Vajrayana path. I began doing more intensive practices and also began the thangka paintings, under John’s suggestion. He remains a revered guide and dear friend.

Decades earlier, in 1969, I had become very interested in the reality of Maitreya, the future Buddha. I remember chanting a Maitreya mantra as I drove through the countryside. At that time, people were saying that Krishnamurti was the world teacher, Maitreya. Beginning in 1970, I attended talks given by Krishnamurti in Ojai, Los Angeles and New York and delved into his teachings. At some point, I no longer felt Krishnamurti was the one I was looking for, although his world view still resonates with me.

During the 90’s, after raising a family, I began a more concerted search for the whereabouts of Maitreya. I came across a few people who claimed they were channeling Maitreya. I even corresponded for a short time with a woman in Australia. Somehow, probably through the internet, I connected with Buddha Maitreya in California and talked with his attendant. Subsequently, I spent a week in Shasta at his retreat center being introduced to his healing tools. I also attended a one day dharshan at Buddha Maitreya’s home in Middletown, California. I personally acknowledged that this person giving the day-long teaching was indeed an authentic teacher. I have been working with his healing tools and have been receiving his teachings for nearly twenty years.

Here is a short piece in Buddha Maitreya’s words and some photos of his various empowerments. He has been widely acknowledged in the Tibetan community. The movie “The Little Buddha” was inspired by Buddha Maitreya’s childhood story. I believe it is way past the time that he is recognized in the West as Buddha Maitreya.

“His Holiness Buddha Maitreya, the American-born incarnation of Buddha Maitreya explains about his incarnation and how the Shambhala Healing Tools he provides help a person develop spiritually, awaken the Soul and make positive changes in their Life and for the Planet, through the transmission of his blessings.

Most of my recognition happens in India, Nepal and Tibet not in the West. In the West, there are many people claiming to be Buddha Maitreya as well as much religious fanaticism. My process began formally when I was 9 years old when Tibetan Masters came to my home claiming I was Buddha Maitreya, the reincarnation of Buddha. My family was very upset by it and forced them to leave. I said very little about it and waited until I was 30 before I was approached by many senior Tibetan Rinpoches, recognized as Buddha Maitreya and asked to go to Nepal. I did this, established a Buddhist dharma center there and was enthroned by many different lineages as recognized reincarnations of many of the founders of each lineage. I am neither a Tibetan Buddhist practitioner, nor do I teach about Tibetan Buddhism. I have been a meditator all my life and suggest simple meditation and living a life of harmlessness as my main teaching. I provide many helpful meditation tools so it is easier to gain the benefits from self-healing and meditation.

People have no idea if a person like me was to incarnate what would I be doing? Yet, I am exactly what I have always been which is a healer. However, explaining how healing actually works outside of new age belief systems, it is hard to get people de-programmed from what they believe is real. Finding out that it is so simple is the biggest thing. There is no real process of indoctrination or belief system, you do not have to join anything or follow. This is all God so it is literally a transmission for you to not have to go through all these processes that you may have to go through if you were doing this on your own.

So I created the tools to make it possible for me to help. I cannot physically help every individual as I am limited just like you are limited, so I put my energy into a science that conforms with the science of the evolution that makes us what we are, which is Geomancy. With the Tools, I use applied geomancy, a level that in time will prove through physics the existence of God, the existence of the Soul and the Etheric Field - the existence of a whole new realm of science that today we call a miracle and tomorrow will just be called the Science of the Soul, Redemption.

With the tools, we receive testimonies every day of people from people who have experienced many miraculous things. A person starts with an Etheric Weaver and they may have never done any healing before, are not doing anything special but they pull it out, it spins around and healings begin taking place and the person starts feeling not only more confident but their emotional body, their physical body, their Soul is becoming integrated and healed. And they start helping other people.

Miracles can be real in our life - not just something that we read about in the Bible and that was then and not today. With the tools, I am manifesting a science to prove miracles exist and that there is a Lord and that the energy behind that Lord has no difficulty in solving all problems. Problems are not there, they just exist due to previous karma and we do not have a way to work out our previous karma.”

Working with the 5 Buddha Families in the Mandala set-up

Five Dhyani Buddhas

When we practice deity yoga or guru yoga we often visualize the assembly of Buddhas, deities, protectors and the lineage teachers. We recite the refuge vows and we invoke blessings and we pay homage and we make offerings, real and imaginary. We may visualize to the best of our abilities the whole assembly as a mandala in structure – an energetic field, if you will. In the very beginning, when Seonaidhe was introducing practices to his students or Sangha, he provided us with this structure.

I would like to discuss, perhaps superficially, the integration of the 5 Dhyani Buddhas and the Celtic Buddist cross, which is our logo. Fundamentally, it is a double dorje within the sphere or environs of a Celtic cross, the union of a cross and a circle.

If we put this cross on the ground as a horizontal disc and visualize sitting on it in the center, in space, surrounded by the 5 Dhyani Buddhas, we have the beginnings of a mandala – a vibrant energy field. The cross can be as expansive as one can visualize it.

In the east, to our front, we visualize Akshobhya, blue in color with his right hand in the - touching the earth - gesture. Bhumispara Mudra. Element of Conformation.

In the south, to our right, we visualize Ratnasambhava, yellow in color, with his right hand in the offering -granting a boon –gesture. Varada Mudra. Element of Sensation –feeling.

In the west, behind us, we visualize Amitabha, red in color, holding an offering (alms) bowl with both hands folded on lap. Dhyanamudra.

In the west, to our right, we visualize Amoghasiddha, green in color, with his right hand held in Abhaya Mudra. Teaching, preaching, fearlessness.

In the center, above our head, we visualize Vaircana, white in color, with his hand held in the Dharmachakra Mudra. Turning the wheel of the Dharma. Form

In addition to direction and color each Dhyani Buddha represents different aspects of wisdom and consciousness, sense consciousness, elements and virtues. Also, each Buddha represents the dispelling or transmuting of certain glamours or poisons.

(The Buddhas may also be visualized with consorts as bringing everything into manifestation. That is to say, the male/female Buddha is complimentary as tantric energy and balance.

In the beginning of our practice session we can visualize each Buddha in the designated direction and recite silently or out loud: Om Akshobhya AH, Om Ratnasambhava AH, etc. to invite the 5 Buddhas to be present in the practice. We could offer a vessel of jewels to each, and also imagine offering a temple of the same jewels enshrining the Buddha. For example, we could offer sapphire and lapis to Akshobhya; amber and gold to Ratnasambhava; garnet and ruby to Amitabha; emerald and jade to Amoghasidda; alabaster, pearl and diamonds to Vairocana or other appropriate offerings.

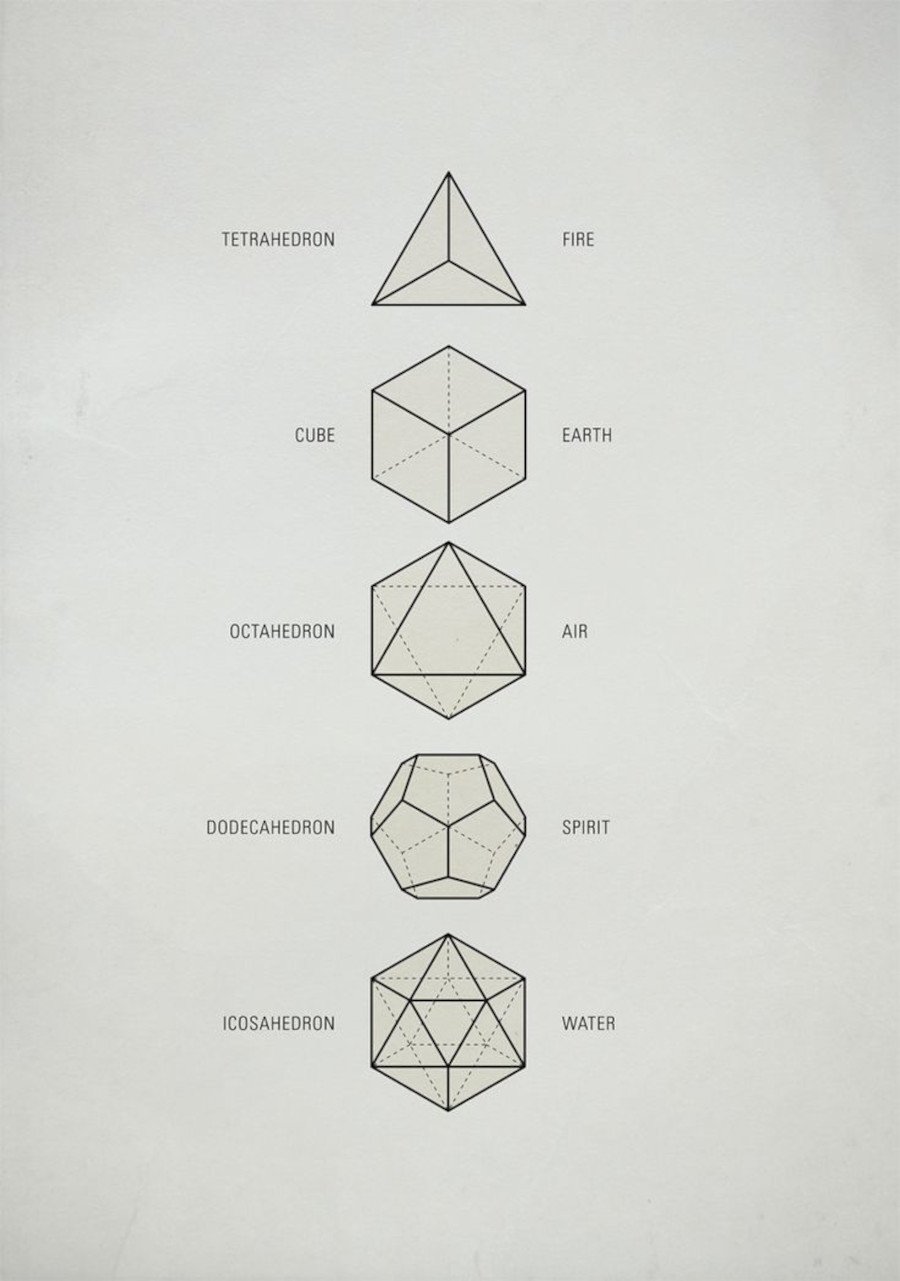

Working with the 5 Dhanyi Buddhas is a healing process, healing all the elements in our body as we express each nature. Each Buddha is a frequency of love and an expression of Wisdom. It’s a matter of bringing that into a radiatory effect as energy or the cultivation of Bodhicitta. Dharma is the Law – a science of transmuting impurities (ignorance, negative pride, attachment, jealousy, and anger/hatred) that may cause harm. These don’t actually exist in the Buddha field. We have the 5 Buddhas representing the elements of water, earth, fire, wind and space (ether). Also, the 5 aggregates: form, feeling, perception, formation, and consciousness.

Akshobhya (Mirror-like) Ratnasambhava (Equaninimity) Amitabha (Discrimination)

Water Earth Fire

Peace Harmony –Peacefulness Right Conduct

Icosohedron Hexahedron Tetrahedron

Winter Autumn Spring

Amoghasiddha (All Accomplishing) Vairocana (All Encompassing –Dharmadhatu)

Air Space

Truth Love

Octohedron Dodecahedron

Summer Open Sky

In the process of manifestation of worlds, bodies, plants, and minerals, there is a progression of geometric forms that build and combine into more complex faceted shapes. These elements are in our makeup and are part of a sacred order. It is not a random process as some might suggest.

This is pretty simplified. People can do their own research and study to fill out the background and to broaden their understanding of what we are suggesting here. I encourage the reader to consider the in-depth writings and teachings of other Buddhist teachers on the subject of the 5 Buddha families and the use of the mandala. For instance, in his many books, Trungpa Rinpoche has talked extensively about these matters.

Here’s a nice, concise link to an article by Thrangu Rinpoche: https://www.shambhala.com/snowlion_articles/five-buddha-families/

Excellent video link on five-buddha families:

Bill Burns

N U B C H O K C H O

by John Cooke

IN SEARCH OF A WESTERN DHARMA

March 14, 2019

In little more than fifty years, Tibetan Dharma has spread through the west, with numerous dharma centers and organizations with highly knowledgeable scholars and practitioners. This is an excellent start in the transmission of the Dharma to the western mind. However, traditional Tibetan expressions of the Dharma will only ever appeal to a certain subset of intellectual westerners.

For the Dharma to be truly established in the west, it must find a skillful form that speaks to the cultural heritage and energetic heart of western peoples.

In seeking what a western form of the dharma might look like, I reach back to my own Irish Gaelic Celtic heritage for inspiration. Origen (d.254 AD) tells us buddhism had been in the British isles prior to Christianity: “the island [of Britain] has long been predisposed to it [christianity] through the doctrines of the Druids and Buddhists.”

An archeological connection for a cultural form for Western Dharma can be found in the meditative Bodhisatva Cernunnos like deity on the Gundestrup Cauldron, seated in lalitasana (royal ease posture) possibility related to Virupaksha, complete with naga, attendant deer, forest creatures, and surrounded by fig leaves resembling ficus religiosa (bodhi tree).

Gundestrup Cauldron

However, through the teachings of the Great Perfection we learn that a literal historical connection is not required in order to employ Celtic mythology as skillful means, as the Kulayaraja Tantra tells us the six types of beings, which includes the Gods, were created by the Adibuddha Samantabhadra, the All-Creating King.

A skillful mythological inspiration can be found in the link between the the sanskrit word Siddha and the Indo-European Gealic word Sidhe. The Sidhe were the ancient semi-mythological Irish people, also called the Tuatha Dé (Tribe of the Gods), later diminished in folk tradition as Irish Fairies, known for their way of living in complete harmony with their environment and reports of their use of magical powers. With the subsequent invasions by less enlightened Gaelic tribes, the ways of the Sidhe became known as the ‘ancient’ or ‘old’ way.

A Sidhe Siddha

FROM THE KINGDOM OF SHAMBHALA

TO THE TUATHA DE SEANBEALACH

With pure view and the objectivity of an outsider, I find it wonderfully skillful that Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche chose the organisational model of British monarchy for founding the Kingdom of Shambhala. This vassalage model, versus the sacred kingship of tribal chieftains, is based in feudal subjugation, empire, and materialism and is arguably the beginning of western societal ills. What a skillful method of exposing the spiritual materialism that is inevitable with the introduction of the Awakened Dharma into a deeply conditioned society.

As I came close to finishing the work on the first mobile Dharma Center, I began focusing on the Sangha aspect of the triple gem and how to express it skillfully while avoiding the neurotic aspects of western society that arose with the loss of our interconnected tribal identity. We would use the enlightened play of “going tribal” to practice pure view and and create an uplifting culture.

To find a name for our community that would attract people to the dharma and pay homage to the Nyingma lineage, I searched the Irish word for ’ancient’ or ’old‘ way which translates as Seanbealach which, not surprisingly, happens to be a homophone of ‘Shambhala’. Our community, from which we would build an enlightened society would be called the Tuatha De Seanbealach, The Tribe of the Old Way.

When I sat and contemplated the vision of Shambhala and an open enlightened society and how it informs the structure of the Tuatha de Seanbealach, I saw a great Bodhi Tree with branches reaching out like an umbrella with deep roots in the Dharma and lineage. Around the trunk are standing stones that represent the cultural forms (clans) that this enlightened society (tribe) displays, such as Western Dharma, Celtic Dharma, Tibetan Dharma, Secular Dharma and so on. While valuable in attracting people to the dharma and affording an opportunity to practice pure view, cultural forms are not the dharma itself and should not be held onto. The Dharma is simply the living lineage that points to the experiential knowledge of the basis of all.

UPDATE: (one year later) In order to throw the largest net while simultaneously filtering casual interest and those prone to spiritual materialism, admission to the Tuatha De Seanbealach has been limited to dedicated practitioners who wish to establish pure view; accept ‘radical responsibility’, defined as the power realized by embracing responsibility for every action we take or allow; have an understanding that western professional and clerical ethics and morality are constructs that may not be compatible with certain practices or presentations; and a proven willingness to respectfully ‘correct the teacher’ which is an opportunity, given by the teacher, to gain merit by correcting an error or pointing out unskillful activity.

Public teachings, and teachings of the children’s sangha will be presented under the banner of the Bodhi Tribe.

Bodhi Bus

BODHI TRIBE NATURE SCHOOL

EXPLORING MOTHER NATURE AND THE NATURE OF MIND

᚛ᚁᚑᚇᚆᚔ ᚈᚏᚔᚁᚕ ᚅᚐᚈᚒᚏᚕ ᚄᚆᚑᚑᚂ᚜

T h e

BODHI BRAVE WAY

᚛ᚁᚑᚇᚆᚔ ᚁᚏᚐᚃᚕ ᚃᚐᚘ᚜

F I E L D B O O K

There is a community of virtuous friends called the Bodhi Tribe.

A member of the tribe is named a ‘Bodhi Brave’,

which means ‘courageous awakening being’.

Their way is:

T h e

B O D H I B R A V E W A Y

᚛ᚁᚑᚇᚆᚔ ᚁᚏᚐᚃᚕ ᚃᚐᚘ᚜

IN THIS LIFE,

I HAVE A PRECIOUS HUMAN BODY.

I WILL TRAIN TO USE IT SKILLFULLY.

IN MY BODY,

I HAVE ONE BODHI MIND.

I WILL LEARN TO RECOGNIZE IT.

IN MY MIND,

I SEE MY FRIENDS, MY FAMILY,

MY TRIBE, AND MY COUNTRYMEN.

I WILL LOVE AND CARE FOR THEM.

IN MY WORLD,

LIVING BEINGS ARE COUNTLESS.

I WILL RESPECT AND PROTECT THEM.

THIS IS THE BODHI BRAVE WAY

THIS IS MY WAY.

Tales of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

by Yeshe Tungpa - Seonaidh Perks – John Perks

Transcribed by his scribe, Nancy Crompton

March 12, 2019

Concerning the Kalapa Court

When we first talked about changing Rinpoche’s personal residence into the Kalapa Court, which would be more of a center where Rinpoche could interact with his students, who would have multi chores in order to serve him, I asked Rinpoche, “So, how formal do you want this?” And he replied, “As formal as you can make it.”

In the beginning, there was just Max King, who was the Chinese chef, and myself. Then gradually, we added people to serve. Amongst the first were Joanne and Walter Fordham. And Mipham Halpern. And Ron Barnstone. Gradually over the months, we added more and more attendants, servers, housekeepers, chauffeurs, gardeners, cooks, and bottle washers, who were all trained to serve using Emily Post’s 1930 edition of the rules of etiquette.

At one point, I complained to Rinpoche that the house was getting overcrowded with servants. There were more than a hundred people serving per week. He looked at me over his spectacles, which was his habit, looking at me for a few seconds before answering, “Then,” he said, “we will just have to call it the People’s Court.”

Awareness training was paramount at the Court, from the way that you wore your uniform, with your polished shoes, to the correctness of your badges, and to the right angle of your cap, and when and where to remove it.

Usually, I awoke Rinpoche in the morning with his tea. He would inquire about who was in the house, and what were they doing, and what was the latest news of the outside world. So I had to have that information readily at hand.

Rinpoche has a bedroom with an attached bathroom and a small sitting room. Since Rinpoche was partially paralyzed from a car accident he had been in, it was my duty to dress Rinpoche in the morning and undress him in the evening, or help him change his clothes for whatever function he needed to attend. Also, I helped him in the shower or the bath, I washed his hair, clipped his fingernails and toenails, sometimes popped pimples, and inspected parts of his body that required attention.

Also, Rinpoche needed support while walking. So we would walk with him holding onto my left arm with his right hand.

Dad’s Tea

Rinpoche often asked me about my parents. And he had conversations with my mother on the telephone. He was interested in her clairvoyance. My father, who was deceased, was a stretcher-bearer during World War I, and I told Rinpoche how my father sometimes made breakfast by boiling bacon and eggs in a pot, and then adding a handful of tea, whereupon he would strain the water into a cup, add Nestlé’s condensed milk, and eat the boiled eggs with the boiled bacon. He learned to do this in the trenches, and there was always a thin layer of bacon grease on the tea.

Trungpa Rinpoche enjoyed this story and many a time he would ask to have a breakfast of Dad’s tea.

Bulletproof

One day, during our retreat in Charlemont, Massachusetts, Rinpoche asked me to buy a revolver and to carry it in a shoulder holster under my jacket. As there had been threats made against his life. Then he told me, while he was trekking out of Tibet and trying to avoid the Communist Chinese soldiers, he carried a Mauser machine pistol in his waistbelt under his robes. I asked him, “If you had been attacked by the Chinese, would you have used the pistol to shoot at them, if your life and those around you had been in danger?” He looked at me and said, “Of course!”

Later on, I was able to find a Mauser machine pistol which I bought for him, and he enjoyed shooting at targets. At one time, when there were life threats made against him, we purchased a bulletproof vest for him, which he wore on occasion at public talks.

Time and Space

Everything in Rinpoche’s sitting room and bedroom was precisely placed and there was no clutter of any kind. This also helped create a mandala of awareness in which your mind was not allowed to involve in discursive thought. Since Trungpa Rinpoche’s mind was vast and always in the present, which is a time and space riddle.

A Personal Note from Yeshe Tungpa

These little stories are difficult to talk about because when one talks about one’s guru, he or she becomes present in one’s body, speech, and mind, which is both joyful and painful at the same time. Joyful because of the brilliant aspect, painful because of the yearning to be in that realm.

Recent writings

Gentleness: Inner, Outer, and Secret Aspects

The inner gentleness is the realization of your body and all its functions being sacred. Sacred in this case means inhabiting a space that allows you sensory perception of your environment in this realm. If you didn’t have this capacity, your perception could be blind and confused. So one has to have a physical body in order to become realized or enlightened in this realm.

That is why it is said, “Human birth is precious.”

Inner gentleness requires that whatever you put into your body—earth/food, air, water, fire, and ether—be also sacred … “sacred” means that one sees the elements/foods as alive beings, one is thankful for their existence, and also their nonexistence, being that they were once alive and are now offering their bodies to you so that you can exist in a sacred manner.

If you defile any of these beings, in any way, then you also become defiled. This does not mean that you should follow some highly orthodox views (however, you could), but simply that you remain aware. Someone asked me once if Trungpa Rinpoche ever hit me, and I replied “Only when I lost my awareness.” Which, thankfully, was not often!

When you defecate or urinate, this is what is left of the beings that have entered your body, and their remains go on to nourish other beings. So you do not want to poison these other beings that will feed on the excrement from your body. You should be mindful and aware of this.

This leads into the outer aspect of Gentleness, in which all beings are treated as sacred. In this instance, sacred means also that all beings can become your teachers. That way, one can acquire much knowledge from even microscopic beings to the largest whales or elephants and learn from how they adapt to their environment, because what you are actually seeing is how a different intelligence can view the environment and pass along the knowledge to you, if you are aware enough and gentle enough to receive that insightful knowledge.

Many native peoples learned from the animal beings living in their environment. It is said Native Americans learned medicine from watching bears eat. That is why bear beings are among the sacred animals of different tribes. As are scorpions and dragonflies and other great intelligences.

Sometimes these secret intelligences might be realized by mishap. That is how Alexander Fleming found the penicillin mold on a piece of bread.

The secret aspect of Gentleness is that it is unknown. That is what is so exciting about it. It has yet to be revealed. And can be revealed if one is aware and gentle. Gentleness does not mean timidness. Gentleness can also mean ferocious gentleness. Which is like when the teacher transmits awareness to the student.

Currently, the Shambhala people are going through a cloud of delusion, corruption, and ignorance. This is because they have neglected kannagara no michi, or the “way of the kami.” The court is the center of the spiritual elements that go to make up the kami of the kingdom. If that is corrupted, even by a seemingly trivial loss of awareness, then indeed that neurosis will spread to all the Shambhala subjects.

Yeshe Tungpa

A Dance of Love - Embracing the Leper

Gryphon Ennis

Every day we have a choice, an opportunity. The opportunity is to live our life honestly or to live it disingenuously. And by “disingenuous” I refer to living a lie. And it is the worst kind of lie, because it is a lie we tell ourselves and others about who we are and what is truth. The greatest gift Celtic Buddhism gave to me and gives to me every day is the freedom that comes from knowing myself and the strength to live out of that.

There are many writings and authorities on Buddhism. But that is not where truth is found. Truth is in the experience of a sparkle of dew on the grass and also in the glint of red blood on a stone. It is in the pain of hunger and in the joy of the warmth of a ray of sun. It is in our hearts. It is what we are when we have dropped all notions of ourselves and hold hands with our clan, with everyone in the universe, with ourselves.

When I first met Seonaidh I had recently left eight years of hard-core Zen monastic training. I knew what a Buddhist should look like, should act like. I knew how to be a Buddhist monk; I had been well trained. I knew how to stand, how to speak, how to chant, and how to meditate. But I did not know what a genuine person was. I did not know, until I met Seonaidh, how to live out of honesty—which is nothing more than the compassion and laughter that arise from humility.

The Celts deeply understood the interconnectedness of life, and so they know humility. A leaping salmon, a dead bull, a rock, a Celt. There is no difference. We all dance together in a dance of love. It is only when we start to put artificial values onto lives and activities that we forget who we are; we lose our humility and fall out of the dance.

One of the quickest ways to become ourselves and drop the facades and games is by following the example of St Francis of Assisi and embracing our leper. St Francis was very afraid and repulsed by lepers, and for good reason. They have a visually frightening, deadly disease and it is contagious. In St Francis’s time, there was no cure for it. Lepers were scorned, feared, hated, looked down upon, and banished from society. It took St Francis many tries before he was able to approach and embrace a leper. But when he finally did so, his entire world changed, because he found himself by dropping himself.

We all have a leper that stalks us. It may be poverty, powerlessness, a bad reputation or being unloved. There is something that deep inside we fear. And consciously (or more often subconsciously) we live our lives trying to avoid that fear. We believe we are not that, and so we run from it. We may believe we are “good” and so we refuse to look honestly at any unkind or selfish thing we do. We may fear poverty, and so we base our actions not in love but out of a need to be rich. It is different for each of us, and yet not so different. We end up living in ways that are disingenuous to our hearts in order to avoid our leper. We end up losing our true selves because we are afraid of losing a false image we created of ourselves. And in losing our true self, we lose our connection to the dance of love. We lose our connection to life.

For me, one of the toughest lepers I ever embraced was admitting that I needed to leave the Zen monastery I had called home for eight years. In asking to leave I was told (and I believed) that leaving made me a quitter, a loser, a selfish person. It proved I didn’t understand the Dharma. It proved I valued my ego over spirituality. It made me unworthy of the black robes. I lost my family, my job, and my home. And all of that was everything I feared being and losing.

But it was the one thing I did right. It was my heart that was speaking, and for once I listened and embraced it. I am not saying it was fun. It destroyed me in a very painful way. But that wasn’t the real “me,” although the pain was very real. The real person we are is the person who cries at the sorrows of this world, is the person who laughs at the joys of this world. It is the person who is not separate from everything and everyone else. It is the being who gives up protecting himself and herself in order to live a genuine life, a life of service, a life from the heart.

Celtic Buddhism requires a warrior’s heart. One cannot embrace their leper without it. But it also requires celebration and joy. Seonaidh taught me that one of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s favorite sayings was “Now this is a cause to celebrate!” Passion is a tantric thing. Celtic Buddhism is a tantric thing. And like anything, its value is in the intent. If there is only pain, if there is not real joy on one’s spiritual path, then it is not a very true spiritual path. Here, one trains hard and one plays hard. It is the Celtic Buddhist Way.

The killing of the frogs at my monastery was the pain that gave me the courage to embrace my leper and find Celtic Buddhism. Celtic Buddhism allowed me to trust myself, to experience (by Seonaidh’s example) what it is to live a genuine life, and to begin to live my own life out of genuineness and laughter. This poem is for the frogs. I owe them and Seonaidh much.

Requiem to the Frogs

soft, cool, wet

glistening like a priceless jewel.

slowly i reach out my hand

to touch you.

Our heartbeats

are the same.

Our flesh

is not different.

I feel the love within you.

Do you feel the sorrow within me?

The abbot says that I must learn to accept

what I cannot change.

But how can we know what cannot be changed

unless we try to make that change

and try and try and try again?

Did Gandhi accept? Did Mother Theresa accept? Did Schindler accept?

Accept??? Let go???

Better to be conscious while feral dogs rip out my entrails.

Better to feel my flesh burn off of my bones.

Better to feel my heart break again in an oh too long life of failures.

and i have failed you today.

and i failed you yesterday.

and i will undoubtedly fail you tomorrow.

I wish you had a better champion than me,

but until then,

i will piece my heart back together one more time

and try again

We are all heroes and villains, failures and victors, sages and fools. All of us. And there is no greater relief, no greater joy, and no greater way to truly be of service than to live a genuine life that springs forth from the humility of knowing ourselves. Stand up with a Celtic heart and face your leper. Embrace your leper and you embrace yourself—then you can dance again.

Working with Ourselves and Others

Peg Junge

Celtic Buddhism begins with developing a deep understanding and

affection for ourselves. We learn to look at our talents, shortcomings,

and inner and outer conflicts with frankness and curiosity. We are

able to do this when we believe what our teacher sees, that there is no

problem and there never has been. From this unlimited view, we find our

personal situation is workable and, eventually, we extend our appreciation

outward to the rest of our world. Celtic Buddhists start where they are, no

longer waiting for a preconceived approval. As soon as we see the need,

we begin our efforts.

On a daily basis each of us interacts with others, so there is an

immediacy and directness to working in this area of our lives. Each of our

meetings and conversations is imbued with energy and potentialities. There

are opportunities to strengthen friendships, increase understanding, gain

insight, and share enjoyment. There are also the less pleasing outcomes of

disturbing thoughts, harming relationships, and creating difficult emotional

states. Who among us has not felt annoyance, disappointment, guilt, or

anger from a short conversation with a friend or spouse? With close relationships, emotional flare-ups can happen several times each day, and on top of that, think about our moments of discontent with store cashiers, coworkers,customers, and even pets! On every hand we have rich and plentiful sources of experiences and practice opportunities for working with others.

There is a tricky side to our aspiration to work with other beings,

because our efforts often contain the seeds of trying to make someone

happy, promoting a religious view, or making our own lives more

pleasant. Any of these and more may be outcomes, but the essence of

working with others does not have a goal. It is simply an outgrowth of

our developing compassion. We find compassion is inescapably connecting

us with our world and we begin acting through it. As we do so, it is

helpful to have guidelines for how to proceed, as our usual touchstones

of Self and its preferences are problematic and best left behind. Instead,

we can use the Buddhist characteristics of generosity, discipline, patience,

and exertion as our reminders in everyday social interactions. They can

be the basis for increasing sanity and enjoyment in our personal worlds.

These virtues, or paramitas, are an established part of the

Buddhist path to realization, which is how I came to learn about them.

There are six of them altogether1 and practitioners work to perfect them

through meditative practice. Originating in the monastic tradition,

the written definitions and applications of the paramitas are traditionally

presented in the perfected form exhibited by an enlightened master.

For instance, generosity is often illustrated with stories of offering

one’s entire wealth or physical body in an act of generosity. Discipline

is demonstrated by years of solitary meditation in a cave, deprived of

warmth and food. Very few of us can relate to these stories of idealized

generosity, patience, discipline, and so on. The paramitas presented in

this way seem to present unattainable goals to beginning practitioners.

Used as reminders, however, their application to our ordinary lives is

extremely valuable and relevant for Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike.

Generosity can be more than giving objects to others. I first began

to see the practical application of Generosity, the first of the six Buddhist

paramitas, while waiting for my husband at dinnertime. The cooking of the

rice, chicken, and steamed broccoli were coordinated perfectly, the table

set, and I was hungry. However, my spouse was puttering at a task and

not responding to my call. As I became increasingly irritated and upset, I

took a look at my clutching to time. What if I gave my time as a gift, in as

generous allotment as needed for my spouse to come to his seat at the table?

We all know about giving gifts of food, money, clothing, and

electronics. But what about generosity with Space, letting others have room

to think, talk, and decide? This is a fun one, as we see if we can let go of

our own thoughts, ideas, and voice, giving the opening to the other person

to fill. Another favorite is being generous with Approval. The craving for

Approval runs deep in us, and without it relationships cease to prosper and

improve. In conflicts with others, denying Approval is a potent weapon and

often the last one we set down. When we work with others, being curious

about how and when we grant Approval offers insights into our generosity.

Discipline, the second paramita, is not reminding us to be

harsh, authoritative, or punitive. Instead, we use it to increase our

ability to relate calmly and helpfully with others. In working with others,

maintaining discipline in what we say and how we act is integral to creating

openness and relationship. Every time we refrain from our impulse to

blame, belittle, scold, or manipulate we are actively practicing the virtue

of Discipline. Just think how many times in a day we are irritated by

others’ talk, their actions, their clothes, their looks! How often are we

offended by other people’s actions and presence, or even worse, being

ignored? If a reminder pops up in our minds to let go of our reaction,

that is Discipline coming to our rescue. When, instead, we respond

with a rant about our boss, a snide comment to our coworker, or a mean

thought about our neighbor, that is the time Discipline took a nap. Put

simply, Discipline is the vigilance that watches and reminds us to put

ourselves to the side and bring Generosity and Patience into action.

Patience is often viewed as a weak antidote for the anger and

disappointment we feel when things began to unravel. “Be patient”

is a remonstrance most of us have heard from early childhood. It might

have been our model car that came unglued, our dog that wouldn’t

behave, or our hurry to finish a task in order to play with friends. As

adults, we need to reacquaint ourselves with Patience and the calm and

space it provides. Patience can be vast, encompassing and allowing everything to exist in its own way. With practice, we can use Patience to allow others to find their own way and events to unfold at their own tempo.

It is quite evident that Patience is not an attribute sought or

nurtured by most Westerners. We have been indulged with promises

of “speedy delivery,” “first come, first served,” and “time is money.”

Finding a way to wean ourselves away from the hurry toward a goal is

a challenge. Meditation is an ideal method for cutting through our

speed and need for forward velocity. With practice, each of us can

become familiar with our mind and its native quietude. Then, when

we are with others, we are able to recreate that mental stillness and

talk and act out of it. The ability to feel the other person’s emotions

and undercurrents are enhanced and communication improves vastly.

There are so many things to be patient with when we interact

with others. Patience as they describe and explain, deceive and manipulate,

accuse and interrogate, push and plead. We need Patience when

anger is directed at us and when our plans are suddenly upended. As

our Patience increases, we are able to remain steady and calm in the

weather systems spawned by circumstances and the beings around us.

Exertion provides the interest and energy that pump vitality

into our Generosity, Discipline, and Patience.

Exertion, or enthusiasm, is the paramita that reminds us to perk up and pay attention.

It is the energy we feel upon arriving at the ocean after a long

drive. We breathe in the sea air, listen to the gulls’ cries, stand in sun

and sand, and feel a surge of excitement. Similarly, Exertion sparks

the curiosity and interest needed to actually relate properly to others.

Too often our tendency is to be sluggish or lazy when we are with

another Being. It is easy to be hesitant, disinterested, or even bored, our

enthusiasm for relating reduced or nonexistent. I’m sure we can all think

of an occasion when this has happened! Perhaps our friend is telling us for

the tenth time about her difficulties at her job, or how she was unable to

find a pair of shoes to go with a new outfit. Our mind just goes to sleep!

Or perhaps our thinking becomes muddled as a supervisor rambles on

with irrelevant information. Instead of listening, we begin to plan out

our next actions on a particular task ahead. The paramita of Exertion

reminds us to yank up our interest and pay attention to what is happening.

One remedy we can apply to torpor or a wandering mind is a swift

cutting through, an instant letting go of one’s entire mindstream. It is a

straightforward action we can all do. Notice the need and just open your

arms and let the grocery bags fall! Enthusiasm and interest will naturally

return and you can start anew relating to the Being in front of you.

Actively working with yourself and others is central to Celtic

Buddhists because it is the pre-eminent way to reduce suffering in the

world. It is all about rolling up your sleeves and getting about the job

at hand. And although most of this essay referenced humans, please

understand we are also talking about properly relating to insects, dogs,

fish, birds, and other living things. Once we realize our close connection

to these beings, we naturally begin to relate to them with consideration,

patience, and generosity. Compassion is the basic condition for

this work, as my teacher Venerable Seonaidh Perks has demonstrated

over and over during the years I have known him. On occasion, I or a

fellow student barraged him with confusion, anger, sadness, or another

emotion. Without fail, we were met with a vast compassionate space

that allowed the whole thing to dissipate and resolve. He extends this

same compassion to bees, birds, plants and animals, as beings equally

deserving of happiness. We are not describing a moralistic Buddhist

“must do” that someone might read about and decide to adopt. This is

simply a demonstration of our ability, as humans, to develop compassion

and extend it outward to all beings, meeting them with active interest

and all-encompassing warmth. May we all become living examples of

compassionate skillful action, increasing the well-being in our world.

*1 The entire list of paramitas is generosity, discipline, patience, exertion, meditative concentration, and discriminating awareness.

"The One Who Hears the Cries of the World"

In the depictions of Avalokiteshvara the central pair of hands clasps the mani, or jewel, to Avalokiteshvara’s heart in prayer-like reflection. The jewel represents compassion, which is his primary purpose. The jewel is held to his heart because compassion is central to Avalokiteshvara’s being. Compassion is Avalokiteshvara’s essence.

I do this work of service because of that jewel, because of my heart. It inspires me, it gives me courage, it shows me the way.

The exterior arms hold a mala and a lotus flower, gifts to the world. Avalo offers these with her compassion extending into the world for all beings. The mala represents meditating with the recitation of the Avalokiteshvara mantra Om Mani Padme Hung, symbolic of the repitition of good deeds in a Bodhisattva’s life. Over and over again we recite the mantra and over and over again we seize the opportunities for service that are presented to us. Service to all beings is our gift to the world.

In the Tiantai school, six forms of Avalokiteshvara are defined. Three of these inspire my practice in Celtic Buddhism;

Great compassion

Great loving-kindness

Lion-courage

Great compassion has been a practice in my life since an early age. My parents taught us that three things were important in life, patience, understanding and kindness. I followed their instruction and example as much as possible. Although not living like a Jain, I respected all living things and practiced compassion toward man and animal alike. As a child compassion was better understood as kindness growing into Great loving kindness and then Great compassion as I grew into adulthood and embraced Buddhism.

Early on it was not the concept of compassion or the ideal of compassionate work that moved me to action but just the basic understanding of who needed help and what needed to be done. I saw that a simple act of kindness that took little effort had great results. As a child it was the usual animals and birds kindness that saw strays and injured finding their way into my heart and life.

Strays and injured soon included humans and I became aware of the opportunity to extend compassion to my own kind. People replaced the fallen bird and homeless people, elderly and the disenfranchised became the strays.

Buddhism came into my life in the 60’s and with it the understanding of the place of compassion in the practice. Suddenly there was the story of Aavaloketeshvara with his head blowing up from the overwhelming presence of suffering despite her efforts and being reassembled by Amitabha as a more efficient and effective warrior against the suffering of all sentient beings. It was all new to me but the idea of your head blowing up because of something struck a note. I read more, practiced more and looked more for opportunities to benefit others. There were homeless people in Boston that gladly accepted food, water, meals at holidays and blankets in the cold. There were shut ins who gladly enjoyed a young man’s company in conversation, over a board game or in the kitchen preparing brought in food. There were young men returning from war who never really wanted to be there and now were happy someone wanted them back either when they got off the bus or when they lay in a hospital bed damaged by the results of their conscription. There were the men who in the 1970’s had to tell their families in one breath they were gay and in the next they were dying from AIDS sitting with them as the ravages of the little understood disease and socially unacceptable lifestyle cast them on the outskirts of society.

It was here that I started to understand Lion Courage.

It is to me the heart of compassionate service. Not that you have to be animal like brave to do it but you have to be courageous enough to witness suffering and not to be discouraged by the volume of it and strive to end the suffering that you are present with.

A life of service is not for the faint of heart. If you do it right, it is selfless. If you do it with devotion it is consuming. If you do it with all your heart it is what matters most in your life. Family and friends have to understand that you don’t love or care for them less you have to share this love, this caring to all sentient beings.

I have always been humbled by the courage of many that I have served at their perseverance in the storms of their lives. Their meeting the challenges even when there seemed to be no refuge. Lion courage is present not just in the giver. This was so evident to me in the lives of the young men, the soldiers and the sick.

In the 1990’s I brought Great compassion and Lion courage to Northern Ireland when I was asked by a small group of mixed faith, mixed heritage Buddhists to come and sit with them in North Belfast and to observe the difficulties and tragedy that “The Troubles” had brought. I made multiple trips to the North and witnessed the death and destruction that the people on both sides of the “Peace Wall” had to deal with. I was fortunate to meet with many people involved in the conflict from Gerry Adams in the Nationalist leadership and Gusty Spence on the Loyalist side, Church of Ireland Primate Robin Eames and people like Emma Groves of the United Campaign Against Plastic Bullets who started the Campaign after the death of John Downes eleven years old killed by a plastic bullet fired by the Royal Ulster Constabulary. She herself struck in the face by a plastic bullet and suffered major trauma disfiguring and blinding her. Sitting in the living room of this mother of eleven children with the softest voice I knew I was looking at the heart of Lion courage.

There were tragic stories on both sides of the wall and in all the sectarian neighborhoods but they shared one thing and that was poverty. Great compassion and Loving kindness was displayed in the soup kitchens and pantries that provided resources and support for the disadvantaged in each community.

Traveling with the Belfast Exposed, a group of fledgling photographers and videographers I was able to witness the results of the hatred that existed between two sides of the same culture and the intolerance of those who were supposed to uphold law and order. Young men and women lay dead in the street or slumped in cars because of the hatred that eclipsed kindness and the absence of compassion by those who were supposed to be trusted by the communities. The courage to be there at that time in those streets was insignificant compared to the Lion courage of those who lived on those streets.

These last years of service since embracing Celtic Buddhism seem mild compared to those years of service in the streets of the 60’s to the 90’s. Gone are the tumultuous times of witness and activism for human rights and dignity now replaced by service to those in the quiet passing of life.

At the same time that I became a Lineage holder in Celtic Buddhism and meeting my teacher H.H Venerable Seonaidh I found Casa Del Asilo (House of Sanctuary) in Bocas Del Toro, Panama a government run, poorly funded center for homeless elderly people. It became the heart of my Great compassion bringing the gift of loving kindness to the homeless elderly people with chronic care who became my Asilo Family following in the tradition of Arya Avalokiteshvara and the teaching of Venerable Seonaidh who challenged me to, "do this work until you drop and do what has to be done from the heart of Avalo”. Spending quiet days in service doing what needed to be done from companionship to preparing the bodies of those who died giving them the dignity that they deserved in death as well as life became my every day.

In Celtic Buddhism the Refuge Chant says that,” “As we become Anam Cara to those in need…” In Celtic spirituality, the anam cara friendship is the essence of spiritual compassion. We are together with all beings in an ancient and eternal bond, the stewards of the compassionate world.

Taking my seat at AnaDaire Celtic Buddhist Center in Saxons River Vermont I am again present with the opportunity to serve those who are hungry, homeless and at the end of their lives. Compassionate service never ends as I will always hear the cries of the world.

May I serve to be perfect.

May I be perfect to serve.

Lama Naomh Tomás Au Flaithbheartbagh

29 July 2015

The Drala Priciple

Bill Scheffel

The “drala principle” refers to a body of teachings the Tibetan Buddhist meditation master Chögyam Trungpa presented in the last decade of his life, from 1978 to 1986. The roots of the drala principle precede the introduction of Buddhism into Tibet and are found in the indigenous traditions of that country—as they are in all countries. The

drala principle is applicable, not to Buddhist practitioners alone, but to anyone. These teachings speak to the heart, whether one is, so to speak, religiously, artistically or politically motivated.

Drala is the elemental presence of the world that is available to us through sense perceptions. When we open to trees, flowers, a creek or clouds we encounter an actual wisdom, though one that is not separate from our own. Beholding a river is much more than merely looking at a river; potentially, we are meeting the dralas. A friend of

mine was once with her family in upstate New York. It was winter and they had hiked into a forest. The landscape was one of cold and snow, whiteness and silence, birch trees. Astonished by the pristine beauty, my friend realized it was her duty—not just to notice this beauty—but to stop and linger with it. To let it penetrate her. To listen. We have failed to see our first responsibility to the world is an aesthetic one.

In the drala teachings, each of the senses is considered an “unlimited field of perception” in which there are sights, sounds and feelings “we have never experienced before”—that no one has ever experienced! Each sense moment, if we are present for it, is a gate into the elemental wisdom of the world; even a cold sip of coffee could ignite the experience of Yeats: “While on the shop and street I gazed / My body of a sudden blazed.” Every perception is a pure perception; from the feel of a meager pebble stuck in our shoe to the meow of a house cat. Through this kind of perception we discover that we live in a vast, singular and unexplored world.

To make a stone stonier, that is the purpose of art.

—Viktor Shklovski

Sometimes a stone, a tree, a teacup or a violin processes an intangible presence, a numinousity, that cannot be explained. The presence might not always be there, or be there for only a short period of time, but that presence may refer to another dimension of the drala principle. Just as our tangible world is populated—and sometimes densely populated—with people and other sentient creatures, the intangible or “invisible world” (invisible to most of us) is densely populated as well. Among these beings, entities, or spirits are classes of beings, or qualities of being, called dralas, also known as katumblies, kachinas, kami, gnomes, elves, angels, gods. Any being who acts on behalf of the nondualistic and compassionate nature of existence could be considered a drala. The dralas are not really part of some other world, but are latent everywhere. The dralas, as Chögyam Trungpa so often said, want very much to meet us.

Using metaphors in the form of words, names and especially mantras or seed-syllables traditionally plays a central part in calling to the dralas, announcing our interest in meeting them, our availability. One example of the fertility of the drala principle is the Ganges River, perhaps historically home to the world’s largest population of dralas. The Ganges is itself a drala. This river, so long adored (and now, like most rivers, under siege by pollution and human disregard of its essential sacredness) traditionally has 108 names, each of them a form of praise and, in that it speaks of a specific quality, the name of a drala(s) as well:

Visnu-padabja-sambhuta : Born from the lotus-like foot of Vishnu

Himancalendra-tanaya : Daughter of the Lord of Himalaya

Ksira-subhra : White as milk

Nataibhiti-hrt : Carrying away fear

Ramya : Delightful

Atula : Peerless

Japa Muttering : Whispering

Jagan-matr : Mother of what lives or moves

Discovering the Dralas

On the most simple and immediate level, the moment-to-moment path of discovering the drala principle might follow the steps given in the Course of Study offered here. Each moment of perception can potentially be experienced as a moment of pure perception—experience not yet mediated through discursive thought and conceptual process. These moments are not yet conditioned by hope and fear, by our opinions, desires and beliefs. This immediate awareness of pure perception is “without choice, without demand, without anxiety.”

Moments of pure perception are experiences of beauty expressed though specific details. It is our duty to notice the details that call to us—any taste, any sight, any sound. This is the call of the dralas.

If we quiet our mind by opening to these details, and if we listen to the response of our heart, we may discover our moment-to-mo ment, day-to-day direction. Thus we begin to follow our heart, to live beyond conditioning—and to be led by the dralas. Not only is our heart the source of our direction in life, it is the source of our confidence.

A Course of Study

Below is a partial outline of some of the topics of study of the drala principle. Each topic is introduced and briefly described, often simply with a quote. (In teaching, I’ve shared these themes—and quotes—with hundreds of people. These words are old friends that I’ve shared with people who have become friends, and that I am now sharing with new friends . . .)

Simply Relax

The experience of drala is as close as our own eyes, ears and tongue. We don’t have to try to taste, say, an orange, we simply need to relax into the presence of the flavor on our tongue and the orange naturally begins to communicate with us. We are generally too active and our own business drowns out the messages of the world around us. To access the dralas we must do less and be more.

Give Yourself a Break

This doesn’t mean to say that you should drive to the closest bar and have lots to drink or go to a movie. Just enjoy the day, your normal existence. Allow yourself to sit in your home or take a drive into the mountains. Park your car somewhere; just sit; just be. It sounds very simplistic, but it has a lot of magic. You begin to perceive clouds, sunshine and weather, the mountains, your past, your chatter with your grandmother and your grandfather, your mother, your father. You begin to pick up on a lot of things. Just let them pass like the chatter of a brook as it hits the rocks. We have to give ourselves some time to be.

We’ve been clouded by going to school, looking for a job. Our lives are cluttered by all sorts of things. Your friends want you to come have a drink with them, your other friends want you not to. Life is crowded with all sorts of garbage. In themselves, each one of these things may not be garbage, but they’re cumbersome when they get in the way of how to relax, how to be, how to trust, how to be a warrior. We’ve missed so many possibilities for that, but there are so many more possibilities that we can catch. We have to learn to be kinder to ourselves, much more kind. Smile a lot, although nobody is watching you smile. Listen to your own brook, echoing yourself. You can do a good job.

In the sitting practice of meditation, when you begin to be still, hundreds of thousands, millions and billions of thoughts will go through your mind. But they just pass through, and only the worthy ones leave their fish eggs behind. We have to leave ourselves some time to be. You’re not going to see the Shambhala vision, you’re not even going to survive, by not leaving yourself a minute to be, a minute to smile. If you don’t grant yourself a good time, you’re not going to get any Shambhala wisdom, even if you’re at the top of your class technically speaking. Please, I beg you, please, give yourself a good time.

—Chögyam Trungpa, from The Great Eastern Sun

Allow Limitation

Limitation is the practice or discipline that supports being. Becoming receptive or open is a natural byproduct of limitation. Meditation is a quintessential act of limitation (though one shouldn’t be hemmed in by preconceived ideas of what meditation is, or where or how it can occur). Even watching a movie requires the limitation of remaining quiet and sitting still. There is, obviously, no better way possible to receive the experience of a movie (though the drala principle is a more interesting movie that costs nothing to see). Accepting limitation is a conscious choice in which we have begun to realize the world becomes a far more interesting and abundant place if we limit ourselves.

One tires of living in the country, and moves to the city; one tires of one’s native land, and travels abroad; one tires of Europe and goes to America, and so on; finally one indulges in the sentimental hope of endless journeyings from star to star. Or the movement is different but still extensive. One

14

tires of porcelain dishes and eats on silver; one tires of silver and turns to gold; one burns half of Rome to get an idea of the burning of Troy. But this method defeats itself, it is plain endlessness.

My own method does not consist in such a change of field, but rather resembles the true rotation method in changing the crop and the mode of cultivation, rather than the field. Here we have the principle of limitation, the only saving principle in the world. The more you limit yourself, the more fertile you become in imagination.

—Søren Kierkegard

[[Please add source info, page number, biblio entry]]

I embarked on two years of painting those paintings, two lines on each canvas, and at the end of two years there were ten of them. So I painted a total of twenty lines over a period of two years of very, very intense activity. I mean, I essentially spent twelve and fifteen hours a day in the studio, seven days a week. In fact I had no separation between by studio life and my outside life. There was no separation between me and those paintings. . . .

I put myself in that disciplined position, and one of the tools I used was boredom. Boredom is a very good tool. Because whenever you play creative games, what you normally do is you bring to the situation all your aspirations, all your assumptions, all your ambitions—all your stuff. And then you pile it up on your painting, reading into the painting all the things you want it to be. I’m sure it’s the same with writing; you load it up with all your illusions about what it is. Boredom’s a great way to break that. You do the same thing over and over again until you’re bored stiff with it. Then all your illusions, aspirations, everything just drains off. And now what you see is what you get.

—Robert Irwin, from Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees.

15

Become Part of a Lineage

A lineage, as the word is used here, means any tradition that evokes and propagates drala. A painting by, say, Paul Cézanne is loaded with drala. A man like Cézanne does not simply happen, but is someone who received the training and inspiration of countless ancestors before him and then put what he received into practice. That Cézanne apocryphally painted until his eyes bled is a measure of the work and sacrifice required to become a great lineage holder. Spiritual or religious lineages have no doubt produced our greatest lineage figures, but the path of drala cannot be defined as strictly sacred or secular. It could occur wherever genuine goodness and devotion are manifested. We might not even realize the lineages we are already part of; anyone who has ever read a poem has made contact with one of humanity’s most universal, primordial and wonderful lineages.

I found no grail. But I did discover the modern tradition. Because modernity is not a poetic school but a lineage, a family dispersed over several continents and which for two centuries has survived many sudden changes and misfortunes: public indifference, isolation, and tribunals in the name of religious, political, academic and sexual orthodoxy. Being a tradition and not a doctrine, it has been able to persist and to change at the same time. This is also why it is so diverse. Each poetic adventure is distinct, and each poet has sown a different plant in the miraculous forest of speaking trees. Yet if the poems are different and each path distinct, what is it that unites these poets? Not an aesthetic but a search.

—Octavio Paz, 20th-century Mexican poet and Nobel Laureate

Seek Victory over War

Chögyam Trungpa initially translated Tibetan drala into an English compound word, wargod. He admitted that this was “not the best translation,” but its provisional use was to establish dralas as “gods who conquer war rather than propagate it.” We can think of dralas as expressions of the fundamental, nondualistic nature of the world; they potentially come to our support when we express the courage to be nonaggressive. Chögyam Trungpa

coined the term, “victory over war” to express a goal of the drala principle.

Just as murder is an extreme expression of aggression, war is collective aggression at its utmost, but the seeds of war are in each of us. Aggression alienates us from the drala principle. Aggression divides people from one another, but it also divides us from the world we are in. War is no longer simply a military exercise; we are so at war with our environment that our very survival is imperiled. So great is this threat that our various regional wars—or even nuclear war—are overshadowed by our environmental crisis. The drala principle requires an honest study and constant unmasking of our own aggression and an allegiance to nonaggression. Nonaggression is not necessarily pacifism, but is an intelligent, firm and awake state of being.

War has an alluring simplicity. It reduces the ambiguities of life to blacks and whites. It fills our mundane days with passion. It promises to rid us of our problems. When it is over many miss it. I have sat in Sarajevo cafés and heard that although no one wished back the suffering, they all yearned for the lost spirit of self-sacrifice and collective struggle.

War’s cost is exacting. It destroys families. It leaves behind a wasteland , irreconcilable grief. It is a disease, and in the night air I smell its contagion.. Justice is not at issue here: war consumes the good along with the wicked. There will be no stopping it. Pity will be banished. Fear will rule. It is the old lie again, told to children desperate for glory: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.

—Chris Hedges, author, former New York Times war correspondent

Discovering That “Luxury Is Experiencing Reality”

The intriguing quote, “Luxury is experiencing reality” is another phrase Chögyam Trungpa used that goes to the heart of the drala principle. In our modern world of technology and consumerism we live tremendously and unnecessarily shielded from the elements; as Trungpa taught, “so many devices are presented to us . . . ten thousand types of gloves and a hundred thousand types of shoes and millions of masks to ward off animals in the real world. . . . Just in case you smell a cow, you have an aerosol.”

Chögyam Trungpa counseled his students that the life envisioned in Nova Scotia must be highly connected to the Earth. We are talking about a farming situation in some sense: how we are going to experience the land properly, the real land, the land that grows crops and the land on which animals are raised. It is very, very important for us as students of Shambhala that when we first wake up in our bedrooms, the first incense we smell is either cow manure or horse manure or the smell of plants. . . . We have to get back and experience how the earth works rather than purely smelling our neighbor’s bacon cooking as soon as we wake up. . . . We all have to work on the earth, literally and properly.

Chögyam Trungpa’s vision was of course not the forced “re-education” of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, but a call for devotion and sacrifice in the spirit of sanity and as an alternative to the dark future facing humanity if the excesses of our age continue unchecked. Quite simply, when we live with awareness of the elements, we live in luxury. Conversely, nearly everything we have come to call luxury is an excess, a distraction, a prison. The experience of rain is one of life’s great luxuries, the source of life falling from the sky! To experience the reality of rain does not mean to go out without an umbrella or a jacket if it is cold, to give up common sense comforts. But the luxuries of the “setting sun” world of modern mass culture is mere endless consumerism based on hungering for ever greater and more mindless comforts and entertainments.

In the following Taoist passage, one doesn’t need to understand its esoteric implications to be moved by its dramatically devastating conclusion.

The fading away of the Tao is when openness turns into spirit, spirit turns into energy, and energy turns into form. When form is born, everything is thereby stultified. The functioning of the Tao is when form turns into energy, energy turns into spirit, and spirit turns into openness. When openness is clear, everything thereby flows freely.

Therefore ancient sages investigated the beginnings of free flow and stultification, found the source of evolution, forgot form to cultivate energy, forgot energy to cultivate spirit, and forgot spirit to cultivate openness.

When openness turns into spirit, spirit turns into energy, energy turns into form, and form turns into vitality, then vitality turns into attention. Attention turns into social gesturing, social gesturing turns into elevation and humbling. Elevation and humbling turn into high and low positioning, high and low positioning turns into discrimination.

Discrimination turns into official status, status turns into cars. Cars turn into mansions, mansions turn into palaces. Palaces turn into banquet halls, banquet halls turn into extravagance. Extravagance turns into acquisitiveness, acquisitiveness turns into fraud. Fraud turns into punishment, punishment turns into rebellion. Rebellion turns into armament, armament turns into strife and plunder, strife and plunder turn into defeat and destruction.

—From The Immortal Sisters: Secret Teachings of Taoist Women, translated and edited by Thomas Cleary.

The above section was written in the 10th century by Tan Jingsheng. It’s called Transformational Writings, and it sums up the Taoist view of the evolution and involution of both individuals and collective processes.

Invoke Astonishment

The following is from the text of a “Shambhala Day” (Tibetan New Year) address I gave at Naropa University in 1998.

The word I have chosen is: ASTONISH. It is a very beautiful word. It comes from the Latin extonare which means “to thunder.” It means to strike with sudden wonder, or even sudden fear. John Lennon said, “Because the world is round, it turns me on.” That’s the idea. Since I thought of this word a week ago—almost immediately after I was asked to give this address—I really have been noticing how astonishing the world is. Every perception that comes to us. A person’s face is astonishing. The way my dog tries to smile at me in the morning by baring his fangs is astonishing. The dentist’s drill is astonishing.

A term in the Shambhala Tradition called The Great Eastern Sun means the world is always presenting itself to us for the first time. Chögyam Trungpa used to begin his talks by saying “Good Morning” because the sun rises in the east. The east is where things are always new. I think he saw his students this way, because when he looked at you he always seemed astonished (even appalled!). Some things are so astonishing they seem uncalled for, gratuitous or almost absurd. A flower!

Moments of perceived astonishment can transform depression and give us real vision. There is a poem by the Greek poet Odysseas Elytis in which smelling the branch of a bush transforms his mind.

One day when I was feeling abandoned by everything and a great sorrow fell slowly on my soul, walking across fields without salvation, I pulled a branch of some unknown bush. I broke it and brought it to my upper lip. I understood immediately that man is innocent. I read it in the truth-acerbic scent so vividly, I took its road with light step and a missionary heart. Until my deepest conscience was that all religions lie.

Yes, Paradise isn’t nostalgia. Nor, much less, a reward. It is a right.

Take One’s Seat

The ultimate purpose or expression of the drala principle is to take genuine responsibility for one’s life. Although this requires sacrifice, it is not a burden but a joy. Becoming responsible means taking one’s seat, but this seat—or throne!—is found in the chamber of one’s own heart. Quite the contrary to what we’re taught in school, where we are often “slowly reduced to disbelieving in ourselves” (Odysseus Elytis, Eros, Eros, Eros, p. 105), responsibility is the fulfillment of our true or fundamental desire, what we irreducibly believe in (even if long forgotten).

Two Shambhala terms are helpful in understanding this responsibility. The first is the sakyong principle. When my son was seven years old, I showed him a photograph of a clear-cut forest and he burst into tears. He cried immediately, inconsolably and seemingly out of any proportion. The sakyong principle entered him, or emerged from him, from his heart. Sakyong means “Earth protector,” a term for the highest seat we could claim, one that is devoted to protecting the Earth itself, and, or course, all the beings that live here. The sight of the destroyed forest—a sight of grotesque unsustainability—evoked from my son an archetypal response of the deepest kind.

The tears of my son demonstrated not only sadness but a kind of tremendous potential energy—so much energy that I’ve never forgotten that moment! We must use the energy-awakeness of the unbidden heart to have the courage to journey toward taking our most deeply human seat as Earth protector: Sakyong. It is seemingly only this kind of collective awakening that will save our planet from continued degradations and possible catastrophic collapse.

The unbidden energy we sometimes feel (perhaps only once in a lifetime) in or from our heart is something more than the constituents of our personality or the type of person we are trying to be. This energy is connected to the ridgen principle, the second pertinent Shambhala term. You could say that, although this primordial energy is not “elsewhere,” it nevertheless originates from a kind of ultimate or unconditioned space (which all spiritual traditions attempt to evoke, understand or at least speak of). In the Shambhala tradition, it is not spoken of, or conceived of, as God, but as the “Rigdens,” the highest form of nondual intelligence or being. The Rigdens are not exactly separate from us, yet we can say—and experience!—that they want to help us.

Rigden means “possessing family heritage.” Our heritage goes back through our mothers and fathers and every ancestral predecessor to the dawn of humanity. But even that is an arbitrary designator, because our genetic heritage not only continues back through apes, but to the original creatures of our Earth’s oceans, back to single cells, to carbon, to stardust. It is impossible not to possess this heritage, but our minds have acquired endless ideas and conditioning that ultimately make us feel alone and alienated from any heritage at all. Existence, in the form of the Rigdens, and in every cell of life, does have an allegiance to helping us reunite with our true family heritage. The ultimate and highest dralas are the Rigdens themselves.

How exactly will the Rigdens help us? There is a simple process we must undertake and in the undertaking help arrives inseparable from the process and perhaps, for a long time, unnoticed. There are steps to the process, though not necessarily in this order:

I. We must recognize our response-ability (to separate the word into its obvious halves). Each of us has a unique ability to respond to our life experience and thus affect the world around us. Not everyone is equal, precisely because there is not a single “ability” to measure us all by. In hitting a tennis ball, some have more ability than others, but this is only one of an infinite number of abilities to possess. Just as we are not all equal, none of us are particularly special, only unique. If each snowflake that has fallen since the beginning of snow is unique, how could each human (dog, cat, tree) not be?

The great Zen teacher Dogen said, “Everyone has all the provisions they need for their lifetime.” Amidst injustice, deformity, starvation, war and poverty it hardly seems believable that we each have the provisions we need. The provisions Dogen spoke of were the ones needed for each of us to wake up, and waking up can never occur from material other than what we already have, however awful. To recognize the material of our response-ability is a lifetime process that is too infrequently tried.

As we do try to recognize and commit to our response-ability, the world offers a response—you could say the Rigdens respond. Small forms of acknowledgment occur; accidents, synchronicities, threads of new possibility. The sense of “moving in the right direction” is palpable though not always tangible; it is a kind of real support that comes to our aid.

II. We must realize our privilege. Most of us living in the so-called first world have tremendous privileges over the greater majority of human beings who live in the so-called third world. A hundred dollars does not necessarily mean a great deal in, say, middle-class United States, but in terms of the overall world economy where the majority of human beings make only a dollar or two a day, one-hundred dollars is a tremendous amount of money.

Strangely, we in the first world often live far more in the grip of economic fear than our brothers and sisters who are making two dollars a day. Mortgages, credit-card debt, home and automobile insurance policies

22

(not to mention the homes and the automobiles), the warranties, deeds of trust, legal contracts, iPod rebates, parking tickets, security clearances, credit ratings, golf course memberships and orange juice coupons become a heaping pile of overhead we feel duty-bound to acquire and scared to death to do anything other than support. And thus our life force goes into supporting primarily these things, making us quite irresponsibly responsible.

That we could leverage our life in an entirely different way—and for very different purposes—is the point of realizing our privilege. Recognizing and acknowledging our privilege takes courage because it begins to dissolve that sense that we are “special,” that we are entitled to what we have and that it will always be there.