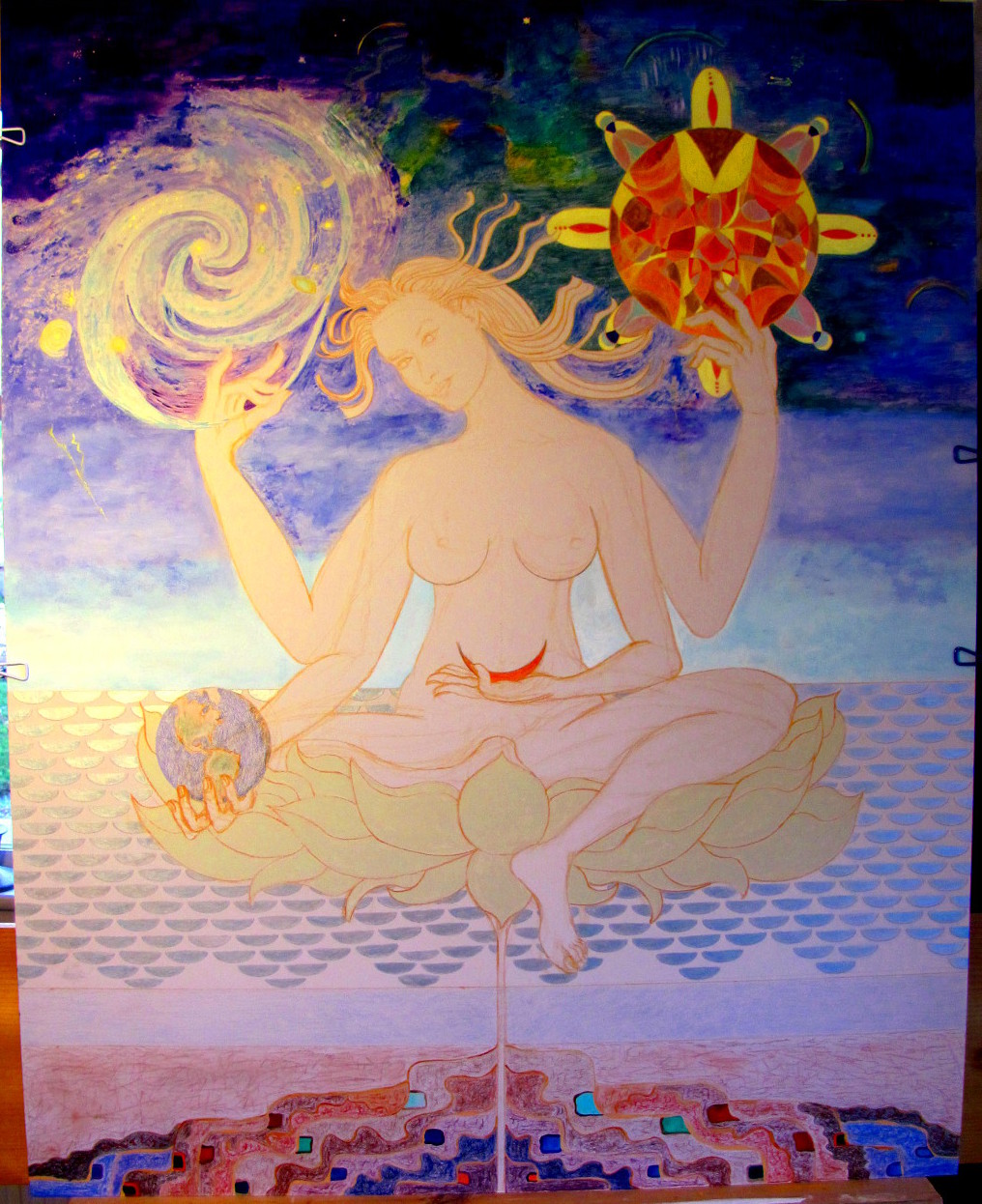

Gallery of Paintings by Bill Burns

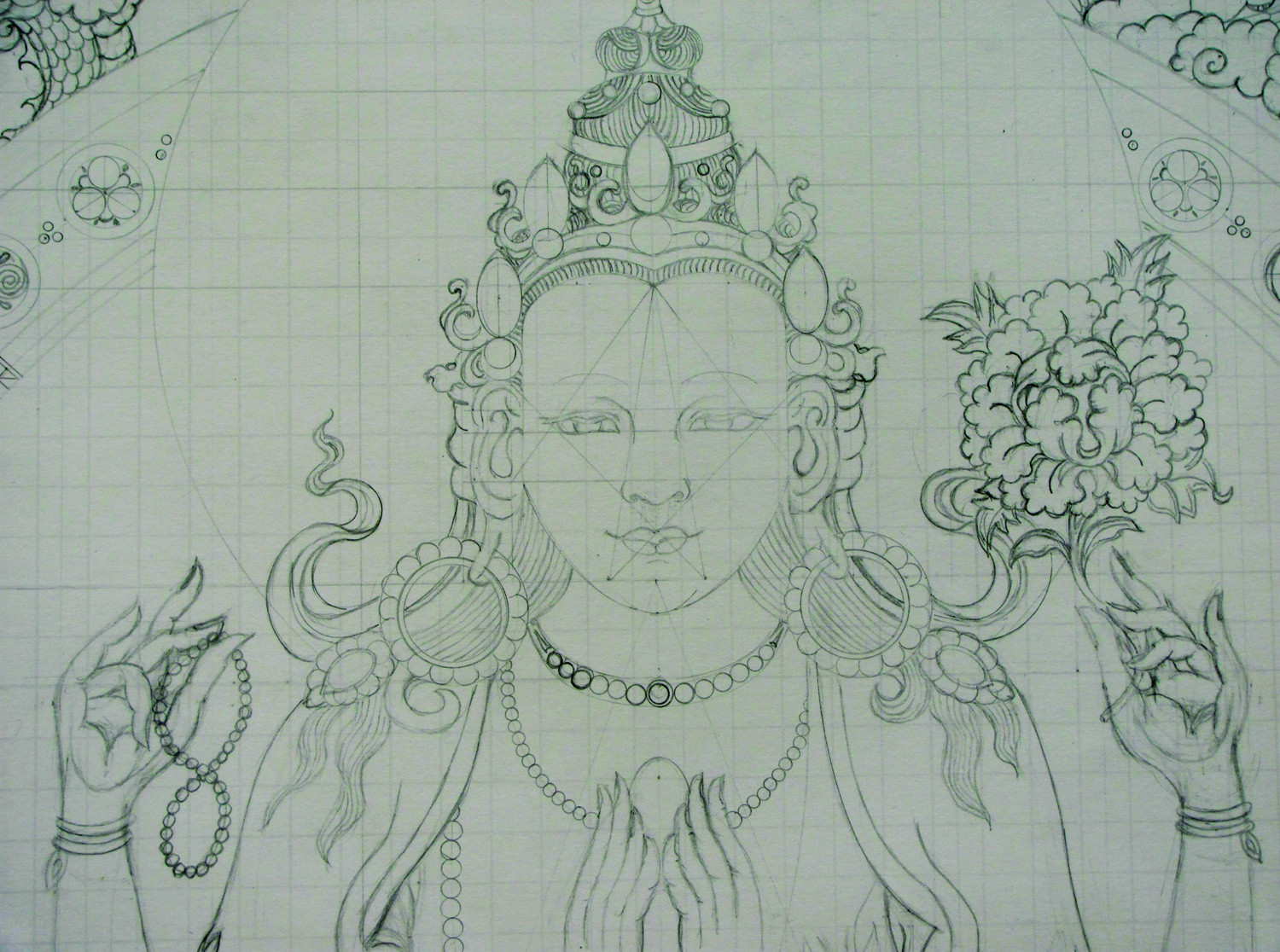

The image is a closeup section of the Golden Buddha painting - Bill Burns

Most of the paintings were completed between 2001 and 2010. There is a written article by Bill Burns titled "Painting the Path" on this page following the images. It describes the process, approach and materials used in doing the thangkas.

Prajnaparamita deity (close-up -Celtic Buddhist Mandala)

Recent painting of the 16th Karmapa (2021)

Avalokiteshvara/ Chenrezig (pen and colored pencil)

Adi Buddha-adorned: 2020

Bear image from a flag design.

Painting the Path by Bill Burns

(Manifesting the Wisdom Mind)

Introduction:

“The path is like a busy, broad highway, complete with roadblocks, accidents, construction work and police.” (The Myth of Freedom – Trungpa Rinpoche p.105)

Celtic Buddhism is not just about being a Buddha in a kilt or finding a Buddha in a kilt, although we have a picture of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche decked out in Scottish military dress on our shrine table. And it’s not just about going to some stone circle and blowing conches, beating drums, ringing bells and chanting incantations to elemental gods, local deities, environmental energies and invisible spirit beings, although we have occasion to do that. It is more about embracing the transparencies of our cultural attachments, to see the splendid richness in an exaggerated form.

When Seonaidh first talked about the Crazy Heart Lineage of Celtic Buddhism he was discussing the activity of bowing to a large convex traffic mirror we had in the shrine room. He pointed out that we were bowing to the idea of unoriginated, unborn mind - unconditioned space that is beyond conceptual mind existing. “When the Lineage becomes an organization we should keep it open.” The whole situation is kept very open so that it doesn’t become a mishmash of superstition or spirituality. We continually explore the openness, which becomes the unconditioned mind. Seonaidh often repeated what his own teacher, Trungpa Rinpoche had said that “cultural attachments are the hardest thing to go through and give up.” So why go into this? Seonaidh explained this in more detail: “You have to go into yourself so that you have some realization of the personal makeup of your acquired mandala. It is not a question of destroying things but a question of recognizing them or seeing them as they are. In this process we are not denying or chopping things off like our mothers and fathers. We are not attempting to disown their particular hang-ups or sufferings, neurosis or joy. But we are recognizing them for what they are and how we are a part of that and how that is a part of our existing mandala as it now exists for us as live human beings. So the combination of the open approach of Buddhism and the existing mandala of Celticism mixed together is Celtic Buddhism. It is just that the actual passion is there rather than someone having an ethnic connection or a dependency on your grandparent’s heritage. It’s your own particular passion and that is what we work with, is our passion.”

“Crazy is more associated with curiosity- having the courage to be somewhat unconventional, impractical or illogical in our approach, a willingness to investigate even though it seems ridiculous.” It involves making a leap into extraordinariness. The “Heart” aspect allows the experience of thinking through the heart. That is, allowing things to come into our particular mandala through the heart chakra and communicating from the heart. It is circulating a quality of basic goodness, of giving out, radiating and receiving.

It is this exaggerated culture or world condition that we feel exploits us and that we in turn as practitioners begin to exploit for the purposes of self-liberation. The context that we seem embedded in, with the entwined history and mythological, fantastic stories of heroes rising to the level of gods along with the whole parade of tribal raids, prophecies, institutions and oral, traditional wisdom, is personified through the arts and crafts of its participants.

The defeated tribes in Ireland, who receded right into the fabric of the earth are still acknowledged and communicated with as the beauty and power playing and manifesting through the elements. How do we deal with the elements, with the natural world, the whole vision of that relationship of the collective leaning toward harmony and balance? How we are to accomplish and maintain this task still lingers in our ideals.

All the disparate movements, group impulses, no matter how distorted and flavored with delusion, still arise from the same basic ground, as does wisdom. Call it the ground of being or the creative source or the undefinable, non-material plenum, it still moves in a fluid, ever-changing, phenomenal display that fashions our beingness, while providing the air and the passion that we thrive on. It is this breath traveling through the spirals and feeding an immense evolution of plurality, dimensions and multitudinous forms, too innumerable to fathom in one glance that ultimately grants us our leave. It is this breath coursing untamed as subtle winds through the subtle channels that is the etheric field of our bodies that furnishes the home movie of our life story. A story line filled with a myriad of environments, conditions, mentally configured and imagined constellations of identities playing out in time and space. In this very instance we can remind ourselves to wake up and manifest as a Buddha. In doing so we are reminding others of their true, original nature. Our conventional mind perpetuates itself by nibbling incessantly on the fodder and scrabble dished up by our educational, media and gossip sources. We are free, but do not realize it, to step out of the reactive process and to be receptive to the wisdom of the whole field of the totality that is present in just this moment. The universal guru is none other than this. You are already the Buddha you are seeking. When you sit on your meditation cushion you are acknowledging that, allowing it to express itself. Your true nature expresses itself, is made known to itself, this is self-cognizing wisdom or insight. This is what is being realized. This is what the teacher always reminds you.

The perceiver or sense of self is an expression of the emptiness aspect of space without definition and the phenomenal world of objects, forms, thoughts and emotions are the reflections that appear as expressions of the luminous aspect called clarity. This then is the duality that fuels the further action and reaction of samsaric cyclic existence. The composites or separate aggregates of this relationship, experienced as identities within their environments accompanied by ongoing attitudes, preferences, concepts and interpretations are not in any way separate from the ground from which they so spontaneously arise. But they are transparent, when seen from the view. The realization of seeing each aggregate as a distinct phenomena and viewed within the context of the arising of a whole unique and integrated moment, seen in relation to the ground of basic space as such, is the development of what Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche called “sacred outlook”.

Samsaric life is reinforced by repetition and familiarity while basic space is apprehended as lacking any inherent properties that the mind could hold onto or grasp. Thus the enlightened state of awakened mind is seen as something of a threat with no specific outline of characteristics. And from those who are seeking some kind of enlightenment or spiritual awakening this space is projected by the mind as an object, in the hope of grasping it. For the samsaric mind there will never be enough good food, wealth, power, sex, or recognition for personal accomplishment.

The methods of meditation which are the devices of liberation are only effective in a

setting where the practitioner maintains an attitude of continued mindfulness and

exertion. In other words, one may lose the initial realization of the view if it has not been

familiarized in the mind stream. When everything is seen as outside the mind as separate

and real, it is easy to get distracted. Our attention gets caught up in attachments of various

sorts and we lose awareness. The whole is displaced by the particular. This has always

been a consideration in perennial philosophy. Intellectually, it is difficult to sort out.

In Buddhist practice these dualities have always been taken into consideration and the

many methodoligies that were proposed by the Buddha in the form of sutra and tantra

teachings have been effective in the past twenty-five hundred years as a path for realizing

the basic nature of mind - the original, unique unchanging nature of primordial purity.

And since the time of Shakyamuni Buddha these teachings have been transmitted by

realized teachers. In this way, Celtic Buddhism is no different. It rests firmly on these

authentic teachings which serve as a support to gradually dissolve the imprints of

delusion which veil the liberated state of simplicity and equanimity.

Today in the Western world we have many excellent and favorable conditions which have evolved in our society which promote the exploration of the spiritual dimension in our lives, and which afford the opportunity to practice meditation. We have a fair chance of being in reasonably good health, with more than an adequate abundance of food, clothing, and living spaces. We have the civil freedoms, educational background and leisure to develop a spiritual path. We have the ability and the capacity to understand subtle metaphysical explanations as well as sophisticated scientific theories like quantum physics. We are well suited to follow the yogic paths from the standpoint of positive karma or merit and to the trends in the present time of a renewed focus on the spiritual to uplift our lives.

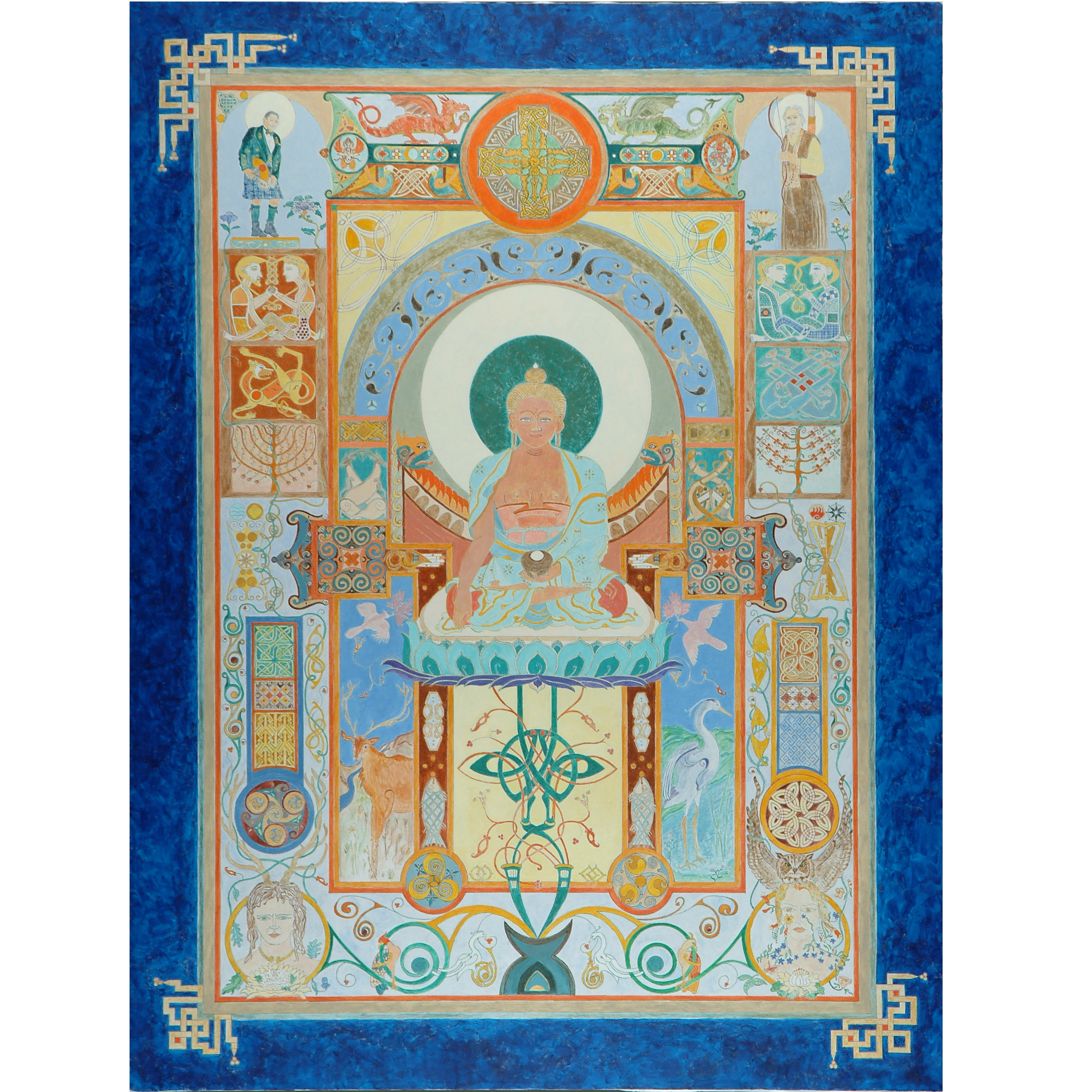

Painting the Celtic Buddha:

“When are you going to start the Celtic Buddha?” John would ask me from time to time. We had finished printing the prayer flags a few months earlier and there were a few flapping in John’s backyard and at our home and at Peg’s sister’s home in Maine. We were going to attract drala energy and magnetize the environs. John suggested designing the Celtic prayer flags depicting the five buddha families by using celtic iconography. We decided to use different animals to represent the qualities: Heron-Vajra family, Whale-Buddha family, Bear-Ratna family, Wolf-Padma family, and Bee-Karma family. John added some Buddhist phrases and my wife, Peg, arranged them into a format and after printing them on fabric she sewed them and thus we had Celtic Buddhist prayer flags.

When John repeated the question of doing a painting of the Celtic Buddha, I would just smile and shrug my shoulders. But the question became more persistent and I believe I had agreed to do a sketch. We had access to books outlining the techniques for painting Tibetan thangkas and we also had books on drawing and constructing the Celtic knots and spiral work that were illuminated in the Book Of Kells. (List in bibliography.)

While visiting my late mother and sister in Virginia for a week in October, 2002 I had the time to make a rough sketch. Using colored pencils, I blocked out the designs and drew in the Buddha sitting on a lotus in the center (Illus. 1). When I returned to Vermont, I eventually decided on a size (?) and bought some canvas and stretchers. The canvas is then prepared with a few coats of gesso and then sanded smooth. Too much texture from the canvas weave will make it more difficult to draw in the fine details of some the designs, Buddhas and deities. In sketching the design on the canvas regular soft lead pencils were used. I found it best to use a pencil type that was easy to erase, because after the inking stage and before painting all the pencil lines are erased. There was a great deal of erasing and redrawing, especially with the knotwork. This segment of the project took about 7 weeks. Many of the areas were measured and worked out and drawn on paper, then, they were traced onto transfer paper and finally were again traced and drawn on the canvas. The transfer paper is taped on the canvas to prevent any movement while tracing. The figure of the Buddha was drawn in accordance with the proportions used in traditional thangka paintings. The Tibetan artists have their own measuring sticks and units for drawing their grids and I merely determined units in terms of my own rulers to match theirs. I studied the various thangkas in books and on the internet to determine some style elements, techniques and materials. In addition, I researched the Book of Kells which was the combined work of the Irish Christian monks in the late 800 AD and the background from which it was created. I remain fascinated and in awe of the skillful and ingenious Celtic artisans and monks who were masters of the spiral, lace and key patterns with their bold arrangements of elemental design. And I was inspired by the playful use of colors and light-hearted flair that demonstrated their relationship or view of the spiritual dimension. This led into many other forays with Celtic mythology and history as well as the designs used by artists and craftsmen.

In selecting the designs I believe some were done out of curiosity to see if I could execute them and some were selected because they seemed to fit into the aesthetic scheme that was developing. Also, my teacher, John, would suggest some figure or personage as for instance, his teacher, Trungpa Rinpoche. Cernunnos and the Flower-faced goddess were also discussed as possibilities.

On the next phase of the work, (Illus. 2) I purchased an array of water-safe, colored pens (Prismacolor) and then redrew the designs over the pencil. I then erased all the pencil work, which turned out to be a considerable amount of erasing, with two or three different types of erasers being used. This phase also took several weeks and demanded my complete attention to be true to my original lines and also to avoid the possibility of the ink running, which occurred a few times. At this phase, one might have to sacrifice the more subtle and graceful pencil lines. I found that the mind had to be very settled to follow a line. As a practice I had to be pretty relaxed and have a quiet mind. I couldn’t do the ink drawing if anything was going on in my environment or if I was distracted by other concerns. I would recommend to anyone interested in pursuing this type of painting to begin with a period of meditation if possible, and perform some purification of the environment and the canvas, as well, by lighting some incense and any other blessing ceremony one is familiar with. Also, one may want to state one’s intention or aspiration to focus or bring one’s passion into the project. I cannot recall at what stage I began doing mantras while I worked. Mantras may be used as a spontaneous device to magnetize the whole situation and thus bringing the mind to focus. I sometimes listened to puja tapes where the mantras would be in the background. At times the mantras were distracting and I just found being quiet a better way to work. I believe there was much trepidation in the beginning of the ink drawing phase. I was aware that I couldn’t make any mistakes. There are many junctures in the process where anxiety or concerns may arise and one has to have the courage to begin and the courage to go to the next step. We have to remind ourselves that we have nothing to lose. If we listen to the mundane mind of everyday concerns we would never undertake and finish such a project. After a while, I began to relax and just allow the drawing process to continue. It was this allowing of the process to continue that brought the painting to life. The different colored inks were not only taken up and used spontaneously but there was also the thinking about where they would go, as well as deciding in the Art Supply Store which colors were suitable. As it turned out the colored outlines that were inked in determined the colors that were used in the painting phase. This was a rather interesting outcome and this process of outlining was an important step.

Also, I had never attempted a painting in this style before. Drawing had not been my forte and I tended toward abstraction and textured surfaces, often layering on paints with metal tools, which are used to apply plaster to walls. The drawing and intricate details were a challenge and required much laboring on my part. But for many years I had been involved and working with the underlying intention to awaken awareness in others through visual art, music, sculpture, theatre, and the environment by creating sacred space architecturally and through the arrangement of stone circle energy, as well. I had touched upon all these areas and I was familiar with the outcomes of these explorations. And thangka painting is in this same field of exploration. It evokes this same intention.

In drawing the image of Cernunnos, I did some contemplation and actually came up with three images, which I finally combined as a composite of that experience. One image was young, innocent looking boy riding on a deer; another was a bit bushy haired and bushy browed; and the third older, darker, sterner, more muscular. Also, in relating to the energy of that archetype, I discovered a very deep dimension, one from which it was not possible to return. And I felt that this archetype connected to the elemental realm, which looks after the natural world. In this realm Cernunnos is the figure-head or guardian of those beings-an aspect of the Lord of the World who directs the deva evolution.

With the feminine image of the flower-faced goddess, I used an interesting photo of a woman as inspiration for the sketch and therefore the sketch had little resemblance to the photo. I did some research into the mythological background of this archetype and her ability to shape-shift into an owl. One of the interesting features was the connection to healing in Europe and the nine plants with their sacred flowers or blossoms. Numerically, there is a relationship to wholeness and completeness and these plants were called the Epiphanies for the healing qualities. And there are other female archetypes that are accompanied by owls, like Athena.

There is a very earth connected feel to this deity, much a counterpart of the green man with leaves and vegetation growing out of the faces – a blend of plant world and the human domain. And also this deity came to represent well-being to me. The aspect of the deva evolution of looking after the plant world that eventually we relate to as health giving or health supporting. She vivifies the budding plants and trees when they are manifesting blossoms and fruit. When we consider the properties of plants and essences made from plants, both as food and medicine as well as the relationship to our senses, this connection and interdependence is often not acknowledged. But it is a factor in our well-being and in our collective evolution.

The other theme that was developing was connected to the tree of life. This element is common to both the Tibetan iconography and the Celts. In the case of the painting, the vase from which the tree or vine grows is a cauldron/chalice shape. The tree serves both the purposes of life giving and the connection underlying everything. There is the hint here of “Buddha nature”, the underlying reality present in all phenomena. As Gyalwa Jampa Rinpoche has said, “The very force of matter evolving, geometrically, into life is Buddha nature.” It also serves the purpose of acknowledging the spark of the divine life force or the creative love aspect that is inherent in the smallest atom (Anu) as well as the human dimension. So the vine grows and it spirals and it has the potential to become anything. It encircles, upholds and touches and enlivens everything. It evolves or emerges from the ground from which all things proceed. In this movement there is an elemental influence, the geometric forces, the forces of sound and color, in other words, the elements. And in the painting there is a hierarchical depiction to acknowledge the unconscious realm, the atomic realm, and the mineral, vegetable, animal, human, buddaic and deity realms. The Buddha and other realized yogis have related stories of having gone through various incarnations of these realms repeatedly. (Crystals are transmitters and receivers (focalizers). The matrixes of crystals follow the pattern of Sacred Geometry. The matrix of grid energy created from a central source which creates the reality in which we experience. The web or myriad of grid energies is the tree of life.

Also, in the painting, there is the feminine side and the masculine and the interplay of the colors to depict or denote this. In the case of the two figures holding hands with their legs entwined there is a reference to the tantric idea that we are both male and female in nature. Thus they are seen as equal in status and a reminder of the union of bliss and emptiness, wisdom and compassion.

There is also the presence of the five elements: earth, water, fire, air, and space. Through these symbols there is the relationship to the five senses and the five Buddha families. Some of the figures and patterns I modified from the Book of Kells with the help of George Bain’s book; and some I merely designed as originals. The basic format that is most notably present in the Celtic Buddha painting is the folio: 28v, Portrait of St. Matthew.

The Flower-faced goddess, often referred to as Blodwedd in Welsh mythology, was the first to be drawn. It was this feminine influence as starting point and inspiration. Also, both the male and female archetypes, as well as other figures and deities, provided motivation and courage to move forward with the project. Since Trungpa Rinpoche instructed my teacher, John, to develop a Celtic lineage, there is a tribute to his teaching and his relationship to the tiger, lion, garuda and dragon qualities known as the four dignities. These will be found in the thangka and they represent meekness, perkiness, outrageousness and inscrutability. Trungpa Rinpoche is wearing Scottish military dress, which he actually wore on occasions and it is an example of the Nirmanakaya aspect of the teacher. Trungpa holds a fan with a dot that represents the unconditional dot in space-the dot of basic, primordial goodness or purity, the origin of everything. I happened to take refuge vows from Trungpa Rinpoche in 1974 and this thangka represents an extension of that relationship as well. Our teacher, John, is on the opposite side dressed in robes. He is holding a bow and appears in his hunter or archer aspect. The large double or crossed Vajra resembling a Celtic cross is the Crazy Heart lineage logo. It is encircled by an orange color, which is the same as the Garuda’s wings. Vajrayogini, a feminine Budda and a yidam of Tantric practices, is depicted in the circle beside John.

In my research I noted that gouache would be a good medium for the painting. The pigments used in gouache have a luster and brilliance of color. The drawbacks of using this medium are that it dries fast and it is not water permanent. Therefore, I experimented with gouache mixed with acrylic medium and acrylics mixed with different mediums to achieve transparencies with the colors. I decided that the way to go for the particular canvas fabric I was using was to apply a new gouache-acrylic product, which could be mixed with straight acrylic colors. I found this to be adequate and later in the process I added a retardant to the paints, which allowed me to take my time. One of the frustrations of paints drying fast is the challenge to reproduce the same value of color when a new batch is mixed. On some areas I favored just the straight acrylic paints. I used a lot of gold mixed in with the colors. Some of the gold pigments had a glossier finish and some a matte finish. When the paints were first applied there was a wonderful brilliance for about ten to twenty minutes, then there would be a gradual fading of the color. Every new color that was applied would change the balance of the whole painting and I would often look for other areas to apply the color once it had been mixed. But one should avoid applying mixed paint to a canvas in an arbitrary way so as not to waste it. It is not a good habit, and doesn’t serve the project. In terms of redoing a color or area that did not seem to fit or work, I believe I only repainted an area on two or three occasions. This condition, of course, had something to do with trying to mix a color to match one used elsewhere and finding once it had dried to be slightly the wrong value. This occurred with a particular yellow. It is interesting to note that when the time came to paint the Buddha’s skin I became overly concerned with getting it right, and of course, I got it wrong. This sort of apprehension about it and the way I applied the paint proved to be the only point where I felt the need to panic. I did some adjustment of the color, but this did not seem to improve things. There was also the concern of whether to shade the features to emphasize the form, but that would have been inconsistent with the rest of the painting. Also, I was beginning to lose the clarity of the line drawing. I consulted a friend who is a master portrait painter. I brought the painting into one of her classes and we discussed what might be done. There was a lot of support from her and members of her class. I went home and later applied some new colors to the Buddha and decided to leave it alone. The Buddha didn’t seem to be too concerned by this arrangement. This brings us to the discussion of the various ways of deciding matters concerning the whole process of the art-work, which I find amusing and somewhat shy to disclose. You may ask the Buddha, or any given deity that you are painting, what he or she would like to wear or include as silks, garments, ornaments, jewelry, hair styles, color co-ordinations, etc. Why? Well, why not. It’s pertinent to the process.

Interesting phenomenon would occur that made the painting of the thangka take on the qualities of a spiritual practice. There was a notable change in the energy in the painting and in the environment when a particular area was completed. For instance, when I drew or painted the offerings that are traditional in Tibetan thangkas there seemed to an acknowledgement of that action. There is a similar response when doing prostrations or making offerings as part of a visualization practice. The same phenomenon might occur when painting and finishing another design or article of the Buddha’s robes. There is a similar demonstration of this in the way ceremonies magnetize the environment. The painting takes on that capacity. So the whole act of painting the thangka was devotional practice involving body, speech and mind. Often the effect of having finished a particular area would bring about a state of identification with the harmony or wholeness that was being manifested and this would bring about a state of meditative awareness. It is that awareness that is present in the painting despite all its myriad forms and colors. So we could say that the thangka might be used as a meditative support. I mention this as a personal learning experience - that a process was engaged in and allowed to continue and that there was some transformative aspect to that process.

Another level of that transformative process was the relationship that came out of the identification with the feminine archetype in the painting that we call the Flower-faced goddess. In our sangha we had been discussing and also working with archetypal Celtic deities in our deity yoga practice. When I began to explore the relationship of emptiness to Shila-na-gig, Vajrayogini, and the Lion-headed dakini and other feminine archtypes, there developed a series of visualizations that eventually turned up an owl-headed dakini. I later discovered that this dakini is actually a tramen or a guardian/gate keeper of one the directions in the Vajrayogini mandala. It occurred to me that this embodiment was related to the Flower-faced goddess who shape-shifts into an owl. Cailleach is also associated with the owl-faced goddess. I had been somewhat exploring the wrathful or semi-wrathful aspect of the feminine archetype as a vehicle for transcending the idea of self or the tendency of self-grasping. Thus, the emergence of deity or dakini is consistent with or in resonance with the mind of the practitioner, arising, as it were, out of space. This space or emptiness, termed the dharmata, allows a form that may transmit wisdom to express itself. This form may be visualized or seen as male or female or it may be some other symbolic form or appearance, perhaps idealized or horrendous depending upon the conditions in the mind of the meditator. In many instances, painting the thangkas helped with visualizing the deities in detail. This is another reason why thankas may be used as supports for meditation. Also, it is my belief that the thangka transmits the teaching of the particular kaya or yana directly, if one knows how to look This may at least be true for the one who painted it. As with most art, we the viewer look at pictures and paintings through a filter of preference, likes and dislikes, thus making it difficult to see what’s there. The thangka may transmit the energy of a particular level of realization - which is represented in the deity – along with the qualities, as well as transcendent insights, directly to the mind. One may indeed realize non-duality while looking at a particular thangka, in the same way one may realize the view while listening to the teacher’s oral instructions or during an empowerment. It is the great blessing that the teacher shares with his or her students that flows through lineage, that keeps alive the vibrancy of the Buddha’s original teachings of Sutra and Tantra.

The outcome of this exploration was the appearance of the Owl-goddess who proceeded to give a teaching based on the practice of offering the body. This teaching contained elements of traditional Tibetan Chod. The practice helps the student in the realization of the identitylessness of self, and identitylessness of other, beyond hope and fear. This is prajnaparamita. As in many sadhanas there are phases where one remains in the view of formless meditation. Also, the unique character of the environment had some semblance of a Celtic nature since there was a cauldron in the visualization. The resulting text was somewhat simplified and presented in English along with some mantras. This process was written up as a sadhana and I then practiced it about once a week for a year. During that period it was presented to some members of our sangha. I found the practice to be efficacious and dynamic.

In general, the painting is a crystallized visualization, but it’s not the only characterization of the deity, or mandalic realm that is possible. It is highly personal in many respects. It helps when one has carefully painted all the details in a painting to then visualize those details during a sadhana or practice. But one is not limited by this depiction. For instance, during a given meditation, the deity could show up wearing entirely different ornaments and garments, or none at all. Yidams may appear in an entirely different hue and in another aspect as wrathful or with a consort. It may be pretty spontaneous. One is encouraged to allow this spontaneity to develop, as it is very magnetizing. Then just treat it as ordinary.

Even though the sadhana is a pattern or structure that one proceeds through, there are instances or phases built into this practice where the whole mandala may disappear or dissolve and shifts into formless meditation. Formless meditation is built into the sadhana. It is an intricate part and outcome, although we cannot properly term transcendent space or nonduality as an outcome. Sadhana has the connotation of endeavoring to obtain a particular result. It is space-like, without definition or characteristics. The mind is not involved in fishing for absolutes, essence, or mode. There is some portion of the path that may be talked about, but the greater part may not be described, though it may be transmitted across mind.

Playing in the mandala - offer your passion to the mandala beings.

The magnifying, enriching, pacifying, or destroying energies could be in each scene. Deities become like family, they accompany you. When you see these aspects in reality, mentally bow. Visualize the deity and give blessings, give offerings or blessings, nothing comes back. One can ask the deities of the outer mandala for help with life situations.

Sadhana is more exploratory than traditional, so you’re being pushed out into outer space, there’s no support system. The sadhana is completely opened and all aspects of deities are individually realized. All the passions, love, anger, motherliness, nurturing, compassion, are found in this particular mandala (1st one John presented), so when that energy comes together in you, you’re inviting from the universe, that allows primal energy to enter your being. From that point of view, you’re doing a purification practice. In this sadhana, all obstacles would not exist in this light frame, they just pop, they just burn up. (In some way this has to do with the mind aspiring to its inherent luminosity factor while practicing; karmic elements are placed at a level of awareness where they dissolve in that space) Cartemandua is pacifying, Brigit is enriching, Morrigan is the destroying aspect that energy that destroys all obstacles like hesitation and doubt, we don’t get attached anywhere. So archetypes may represent processes in the psyche. They may stand in for universal or fundamental principles that are difficult to conceptualize or explain. Therefore, a dark-blue deity may represent Unconditioned, Absolute, Abstract Space as a way to relate directly to that space. In this sense, it may be said to be a “path of contrivance”. But in this case, tantra, the contrivance is efficacious and useful.

As one does the practice, the aspects or character of the deities may change and they reveal specific natures. One’s intuitive realization is allowed to grow. Realization of Prajnaparamita is realization of the whole thing, as well as the realization of the feminine quality of the Prajnaparamita in a primordial way. One needs to be mindful and also have a close rapport with the teacher to discuss what comes up in one’s visualizations, and any difficulties one encounters. All kinds of obstacles may arise, energies may be shifted and integrated, dissipated and transmuted.

For the occultists in theosophical discussion, space is an entity. I cannot really counter that assumption, I believe the Buddha might not have taught that summation, that the activity of space would be encompassed or inhabited as a being.

Certainly such a being would hold all views equally. Its consciousness would be comprised, at least some consciousness, of the summation of all views. But from an individual’s perspective, we tend to feel that our own one, tightly held view is synonymous with God’s. It seems to be a cosmic joke, although a sad and profoundly detrimental reality, that men like to kill each other at the drop of a hat for proclaiming a view that may be different from theirs, particularly if it’s about their god or an absence of a god altogether.

Signing the thangka with your name in the corner of the canvas will probably imperile the process, so it’s not recommended. The painting practice is in the nature of an offering. Like doing one big, long prostration while holding in one’s outstretched arms a golden chalice that contains the whole universe. When the painting is near completion, mantras are drawn or painted on the back of the canvas in their appropriate places. Then a ceremony of consecration is performed to bless the painting, and finally the eyes of the main deity are painted in.

The pilgrimages we took to Ireland, the building of our own stone circle at Anadaire Buddhist Center in Vermont, the retreats in Maine and the ceremonies we performed allowed us to re-enter a mythic journey, on the level of archetypal consciousness where the deity realm is found. And this is a realm or interface where wisdom and energy is conveyed and shared with the human realm – a space of separation gets crossed or bridged. The early Irish monks like St. Brendon and St.Columba, and St Kevin of Glendolough were very much like the Buddhist mahasiddhas of Tibet and India. They were amazingly ready to surrender everything in their new quest. In this transition from the influence of the past, the saints and mystics took over the roles of the heroes. St. Brendan’s legendary voyage in a leather coracle, long before Magellan sailed to the far corners of the world, became the stuff of myth. St. Kevin, who lived in a cave above the upper lake in Glendolough, once stood in the waters of the cold lake while holding a bird’s nest until the egg hatched. And St. Columba, who conversed with angels, slept on stone floors, and subdued a sea monster in Loch Ness, adds to the tales of the fantastic. The Irish monks would embark in their leather coracles and set out to sea; wherever the tides would take them. When they landed, they would bless the land and set up a monastery. They loved poetry and they experienced the divine in nature, often inhabiting remote islands and, somewhat forced to practice asceticism, they endured their holy plight. They are revered because of their intrepid devotion to a desire to commune with God. No less so than Milarepa, and other Tibetan mystics, who subsisted on nettles and lived in caves until realization had truly dawned and they determined they could honestly and effectively benefit the lives of others.

Why Celtic Buddhism?

There is the notion of “Auspicious coincidence” which you have regarded as important or valid to your particular journey. I had in the years 1965-1969 worked as a teacher/house parent at a private residential school in the Adirondack Mountains, and as a counselor at a summer camp, which were coincidentally co-directed and founded by John Perks. We worked with children with emotional difficulties and learning problems and later on there were more teenagers with delinquency backgrounds. I enjoyed my years with John participating in many of his zany shenanigans and mock battles and mountain climbing expeditions with students and staff. And I learned a great deal in the many group meetings that would morph into therapy sessions. John was fond of pageantry and he was always imaginatively creating some activity to bring some rollicking fun into the moment. In this he has not changed and I suppose it is one the reasons I have walked along with him on this venture. I saw John on and off during the 70’s and by that time John was Trunga Rinpoche’s student and later became his valet or attendant. I went off and started a family and bought a farm, so there was a period of over twenty years when I did not know the whereabouts of John. My wife and daughter and I, and later our son, moved to Vermont in ’97. I was quite surprised in ‘99 to discover that John was living just five miles north of our house off the same road. I had seen a flier mentioning Celtic Buddhism and the name of a teacher, Seonaidh Perks. It was the first time I’d seen the name Seonaidh. I was pretty sure who the character might be. When we first met together for lunch and traded life stories, as I recall, I said to John, perhaps we could get together and sit. Thus I began attending John’s talks along with my wife, Peg, and we both became John’s students and Celtic Buddhists by default I must presume. I had no prior interest in Celtic lore, I liked Celtic music, but I knew little about an in depth familiarity with the mythology or historic development of the culture. I had been to Scotland in ’95 to attend my niece’s wedding.

Shortly thereafter, I accompanied John to Ireland, where he had been invited to teach in Dublin. We had an enjoyable trip, meeting Buddhist students and socializing in the pubs. It was my first acquaintance with Ireland, one where I experienced a visit to Uisneach, an ancient royal seat in Meath referred to as “the eye of Ireland”, and to Glendolough, the location of the monastic center founded by St. Kevin, a hermit mystic of the 4th century AD. I had some powerful experiences in both places. The impulse was present to tune into the land and its energy, to be in resonance with all that took place there. There was a mutual radiatory healing taking place and a recapitulation of former teachings and realizations. The dakini level presented itself, in the people whom we met, along with the different sacred circles and stones, in the lakes and ponds, in the herds of cows and the dogs. Because of our Buddha nature, our relationship to the phenomenal world and our actual union with the source of these energies, we all have the innate ability to bestow our blessings on everything in our life situations. This seems to be spontaneous. Since the late sixties I had been naturally drawn to power centers and sacred sites. I discovered along the way that I could feel and locate precisely where conduits of energy were coursing. These are often referred to as ley lines or the Earth’s chi, along with their nodal points or portals where the different dimensions of reality may intersect. It is held that the sacred sites correspond to the acupuncture points of the earth and the land. At these vortices of telluric energy there is the opportunity to bask and be healed by this force. And the ancients, we especially find in Ireland and all around the world from the past 40 or more centuries knew and experienced and valued the properties of these places. It may be said that in some cases the site held these energies like a natural wellspring and in other cases for ritual purposes those sites were created and became magnetized by their ritual significance. But both of these alternatives were exploited by the mound builders, the pre-celts and later, the Celts and Christian Church, in directing, focusing and utilizing the telluric forces that streamed into these areas. They became places with the potential to shift consciousness into another register.

It was also during this trip to Ireland that John presented publicly for the first time a sadhana he had written employing Celtic and traditional Indo-Tibetan deities. This was our first introduction to the celtic mandala and to a more sophisticated visualization practice. In practicing the sadhana, I found it to be a dynamic venture into the involvement with archetypes and their utilization in transforming psychological energies. When John presented this material in Ireland those who had some familiarity with Buddhist doctrine and practice were generally unsettled by this material and more resistant to embracing this form. Some people in the United Kingdom and Ireland are more protective of and sensitive to the Celtic heritage, as one would suppose, and many more are eager to transcend and abandon this heritage, which is also understandable from some point of view.

Patrick preached against sun worship. It may be said that Patrick’s effectiveness in supplanting the druids as a spiritual influence rested on the fact that the druids may have reached a stage where they placed more emphasis on their idols and images and less on personal realization. In the beginning of Irish Christianity, and invested in the many saints to follow in Patrick’s footsteps and aura in Ireland, there arose a fervor or ardor that held a new kind of redemption and inspiration.

This purer version or sacred treasure, which was taught and received long before Patrick, was the religion of the Bible and the Apostles. It was what the early monks referred to as their standard of faith, found in scripture, and this was exemplified in the decorations of the Book of Kells which was a sort of visual aid of the liturgy to those who could not read. And St. Colum Cille was able to render and interpret the sacred scriptures in a more clear form because of his divine vision and expansive contemplative nature. Thus the Book of Kells became the illustrated guide to the bible for the times.

Already, when one hears the term Celtic Buddhism, one wonders, “How will I fit into this paradigm?” Moreover, “how will I apply it in life?” Which leads us to the task of conveying some quality, from our perspective, of this dilemma, being that one need not fit oneself into any paradigm at all and one need not wrap some neat and proper paradigm around Celtic Buddhism. Some people laugh when you mention the term to them as if there is a joke planted there. Actually, we find that those who feel an affinity with things Celtic and those who feel an affinity with some aspect of Buddhist philosophy and meditative practice may be drawn to investigate Celtic Buddhism. But there are many who cannot bring themselves to mix these streams for concern that one will distort or dilute the other. There is a fear of blending. Bodhidharma didn’t go directly to Japan and start Zen Buddhism. He was originally from India, under another name, and he was sort of vacationing at the Shou-Lin monastery in China, where he decided to sit down and meditate in front of a wall for a decade or so. Then from that action, and the realization and inspiration it engendered in others, we have the beginnings of Chen and later Zen, and perhaps the beginnings of the martial arts as well.

Some of our heritage is in fact Celtic, genetically, biologically, but only partially. We are not trying to make a case for geneology. It is that our Western culture and collective consciousness derives some structure from the Indo-European influences, of which some are definitely Celtic. Be it found in mythology, children’s stories, songs, dance, food, plaid shirts and scarves; a leaning toward a belief in fairies, leprechaun fetishes; the sacred art and knotwork of the monks, the tales of the Irish saints, the tales of King Aurthur and Merlin; dragons, druids, the Tuatha de Danaan; or the pantheon of gods and goddesses of Europe and the British Isles that are attributed to some Celtic affiliation, none of this is exclusively Celtic, but it rides on the long and sweeping dragon’s tail of what has been known in the coursing development of “Celtic”.

We are told that the Celts favored a view close to a nature mysticism that sees God or some sacred essence in nature. Still, here we are in the 21st century, all fishing for the salmon of knowledge, either sticking our hands into the swirling waters and hoping to come up with “the fish” or casting about in the still pools and estuaries waiting for a bite. A wonderful vision to imagine is catching a wonderful vision. Celtic Buddhism is an intermingling of the open-heartedness of Buddhism and the open-endedness of the spiritual quest with the integration of living the mythic journey. There is a possibility of encountering the goddesses that we imagine as external forces.

In Buddhism, these things are no longer separate, they are actual contrivances employed in the transformation of psycho-spiritual energies. I don’t ask that anybody join or suddenly jump on the bandwagon as a new movement. It is, for me, a continuation of my earlier philosophical studies, esoteric practices and contacts with yogis, theosophists, J.Krishnamurti, and Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. I can not stress enough, as other teachers have done in various lineages, the need for a teacher who points out the view and also cautions one in a sometime painful way of misusing the teachings. It is most important that we find some teachings that resonate with our own spiritual temperment. One should look for a teacher who empowers his or her students to explore further, and at the same time to keep it humorous, light, and free of too much self-importance. I’ve been fortunate to find such a teacher in Ven. Seonaidh (In Ireland, John’s students call him, Seoanaidh, almost rimes with Johnny).

We call John, Venerable Seonaidh, out of respect. We respect him as our teacher, and as such he is someone to be venerated. We value the ceremonies we’ve shared with him, as well all the meals we’ve shared that he has cooked for us, and the many glasses of wine we’ve toasted to our mutual well being. John’s approach to ceremony has always been creative, spontaneous and respectful of all the energies participating in the situation. John’s teaching has always emphasized and revolved around the essence of Prajnaparamita; he’s always teaching the view, properly and traditionally. Also, we have many practices that are unique to the Celtic Buddhist lineage. John has been very careful in the timing of his teachings and at the same time, very generous. As someone whom I entrust to call my teacher, I have found Venerable Seonaidh to be bold, yet also extremely careful in the way he transmits the teachings. And he has not allowed his students to worship him as someone on a higher plane. He walks next to them as a spiritual friend and at the same time, a few steps ahead to entice them to go further. In his inspiration or suggestions over the years he has been peerless in his role as pointing the way, suggesting that I paint the Celtic Buddha. Out of that came the Mandala, then Vajradhara and finally Vajrayogini. John had the courage to establish a new lineage, and John’s aspiration is to serve, to help mankind awaken. He’s more patient than I am in this endeavor and responsibility, and he continues to be creative and open in his approach to interested students and in the way the teachings evolve. John has a natural gift for encouraging one to take one’s experiences as the path. This integration is unique and not formulaic. Again, it’s John’s natural gift and insight. It is even a bit of luck for a teacher to find even one worthy vessel to pour the teaching into. We hope Venerable Seonaidh is fortunate to find many students who will benefit supremely from his teachings.

Many meditative minds have the capacity to be imitative, but few have developed insight or intuition. It is not that such individuals lack diligence or devotion, but perhaps spontaneity and the willingness to be unknowing: to be without certainty. Such people rely on knowledge and demonstrate their knowledge of the practice but not the realization. They become experts and gather round them many bedazzled students, but it is no guarantee that these students will receive any genuine transmission. A true teacher transmits wisdom from the wisdom mind, it is therefore enlightening and unattached to any outcome. It holds the seeds of true liberation, which may or may not be recognized by another. In most cases, it is not felt or detected and the teacher is treated as ordinary. This scenario has repeated itself throughout the development of lineage in the wisdom traditions. Those who rise up in the ranks of organizations often become dogmatic and become rule makers and enforcers. Occasionally, one of their ranks will experience genuine, authentic realization and may pass it on to one or several students. This case has been more rare than common. We often find some authentic, independent teachers being discredited by those who consider themselves to be the organizational knowledge holders. They make proclamations and deem that another teacher has no abilities to transmit the Dharma. They do this by some manner of authority, which they extend to themselves and that other people take to heart. They make those who might have a heart connection to the authentic teacher feel frightened or condemned. Excommunicated comes to mind. It is only natural to feel that the teachings will be corrupted and distorted, and one can understand the inclination to be protective of the teachings. When all has been said and argued, one has to consider it good fortune to fine a genuine teacher in this world of confusion and misconception.

We have and always will be manifesting our most heartfelt aspirations, the ones we repeat to ourselves automatically. Our commitments to what we want to manifest and realize become refined over time. That seems to be part of the journey aspect. The objectives and focus that we may foster on behalf of our heart’s desire is tied to the way our passion moves and operates in the world. With the presence and blessing of the Teacher there is a sense of lineage with the Buddhas, enlightened beings in an unboken lineage back to the historical Buddha and with the league of awakened ones who compassionately aid mankind and those who seek liberation from the cycle of samsara. These spiritual allies include the Bodhisattvas, who endeavor to practice and teach for the purpose of benefiting others. In the path of the Bodhisattvas there is the renewal of aspiration from lifetime to lifetime, and the recapitulation of abilities, merits and realizations that have accumulated as part of the journey.

The influence of the teacher, as antagonist, as encourager, guide, one who suggests what to address as a path is important because this person has walked on the path and has an accessibility to and familiarity with its features. When people work on themselves, they may address their emotions, life interests, habits, at an intensifying and ridiculous level. Side by side, this investigation includes the mundane flatness, dullness, or solidity of everyday situations, which we often find unbearably heavy and monotonous. We may remind ourselves that the blessing of the teacher is foremost in all of this. The transmission or empowerment from the teacher brings one around to a state of meditation. This crossing over may happen in intimate or casual everyday relationships or in more formal ceremonial settings, as well as during practice.

Inherent in the recapitulation process one may find latent stories, initiations, undertakings, vows and heroic adventures, which have been moving humanity to create an environment where Buddhas may be born. That is to say, when a being takes form here on Earth, that being is a Buddha. He or she doesn’t have to seek out a path to attain this, one is a Buddha to begin with and thus dwells in this sphere in some form which is experienced by another Buddha. This created environment in this dimension which may sound like an ideal, however it is as actual as any other ongoing reality we may be experiencing.

The notion of incarnation may be believed or not believed. Some repository of consciousness, the seed instincts of the skandha process, transmigrates and then ripens under the right conditions. The potency of these seed instincts is underestimated, (tiny specks, the residue of unlimited mind, expand into mandalas of world situations). These karmic accumulations increase and as seeds, given the right conditions, mature, and create life experiences. And more importantly, so does the merit derived from good works and good intentions, meditation, service to others, and the representation of our virtue. Also, out of this there is produced the situations where we meet teachers, hear the dharma, have enough leisure to meditate, have good health, education, etc. We already have the ability to heal oneself and others. These abilities are triggered by meeting someone, going to a particular place, meditating in a holy cave, reading an idea in a book or intuit in meditation. Virtue begins to express itself and old habits of body and mind fall away. We renew the wish to help others, to heal others, to create an atmosphere in which everyone on the planet, all beings everywhere for that matter, begin to share in the awakened state. The karmic accumulations in the system experienced as afflictive emotional states obscure the natural radiance of mind as the source of compassion. These are not permanent or unchangeable. The psychic imprints of these karmic instincts may be dissolved and liberated. This is certainly possible, and the imprints may accurately be called illusion. In meditation practice, one develops the insight that brings about the transformation of all the processes of Consciousness and makes clear the underlying mechanism of karma-creating activity. When this process is seen clearly, one is relieved of the continual self-imprisonment by self-delusion. The particular is still regarded as precious but it seen from a more spacious and unfettered state. Liberation does not happen according to what the mind knows or has read about liberation, so hitch your wagon to shunyata.

If we are lucky, from lifetime to lifetime we are reminded of our aspiration. When we wish for all beings to be awakened completely, to realize their Buddha nature, we are creating an environment where all beings may be born as Buddhas. If you want to include war and pestilence in your aspiration, then so be it, but who or what is making this assessment?

Some minds look at Celtic Buddhism and feel there’s a need to fit two disparate systems into a neat interlocking whole. However, consciousness is already a moving continuum- a whole. This larger sphere of knowingness accommodates many collective and individual changing states of consciousness. Celtic Buddhism is just one of these movements that acknowledges and reminds beings of the wholeness aspect or the complete openness aspect. Many people are just interested in finding an historic link between Celtism and Buddhism. Although one may find information to derive and establish such a conclusion, for me, this is not the crux of the attraction to the path. Those who are just fascinated with historical validations will probably not be satisfied to look deeper or to look at this from another perspective. Karmic associations already abound and one may spend too much time in speculation considering if a viable spiritual path indeed exists. Although it is good advice to be skeptical and consider these ideas carefully, it resembles scientific parties convening to determine whether there is global warming or not. One has to decide sooner than later, because the phenomenal world is rearranging itself. WHEN ONE CONSIDERS ONE’S LIFE AND THE CURRENT WORLD CONDITION, THERE IS AN URGENCY TO AWAKEN. One already has this Indo-European cultural background so it need not be manufactured. One just has to immerse oneself in the Buddha’s teachings and purify or transmute the kleshas and attachments and allow the awakened state to manifest. There is basically nothing new in that. By virtue of skillful means, out of the mandala of the teacher, will arise teachings that will effectively address the different spiritual instructions or approaches that will inspire and liberate the minds of the students. That is the theme of this discussion.

The propensity of past merit- which is seen as good, by the way - flowers or is triggered when one reads a line in a book, watches a movie, or sees a teacher, icon, enters a sacred site, power center, stone circle, pyramid, mound tomb, monastery, or perhaps just by meditating. One begins to recapitulate the initiations and teachings that have been the stepping stones of one’s spiritual path and unfoldment. When this begins to occur, it follows that various influences come into play and one’s life may be shifted. Virtue opens up and common sense manifests. If one had spent time in a former life meditating in a cave, one may have an urge to do so. One may feel impulsed to venture into new territory, like go to a different section in a bookstore and buy an occult book, or one on mysticism. Common sense allows one to step through the bars of one’s personal and collective self-imposed imprisonment and limitations and to see how to change life. One could just put down his rifle and walk away from the battle, one sees the absurdity and suddenly the stupidity of the actions of men in the world. This is dangerous ground, it is innocent ground, with the implication of a world shattering action, greater than any missile launched in the name of peace keeping.

In Recapitulation, we are reminded of the notion that when we go to certain places around the world-the Hill of Tara, Maeve’s Cairn, Lough Crew, Glendolough (St. Kevin’s monastery), Iona (St. Columba’s monastery), Jerusalem, Bodh Gaya, caves in Nepal, Bhutan, and Tibet - we recapitulate certain teachings and initiations that took place there. That’s basically what the Tulku does when he or she is discovered as a little kid living among nomadic people in the high plateaus. The child is brought to the monastery, he recapitulates, he has his belongings there, ritual things he liked and used. He recapitulates merit – his ability to heal, to transmit Dharma to awaken others. So everybody has that. When we go to the pyramids, or Delphi in Greece, to Stonehenge, a Kiva in the southwest –we reinstitute, we reignite the blessings and realizations of another time. This occurs when we read a text or practice a sadhana. In the case of Tusim Khyenpa , the first Karmapa and first recognized tulku, it is said it took him a week to realize the attainments of Naropa’s twelve years with Tilopa.

We walk around, the truth eludes us, primarily because the attention aspect of the mind does not hold still long enough or look in the right direction. That is mindfulness, examining what’s there as the mind, the nexus of consciousness, and its automatic processes. Perhaps throwing the right question, asking, as the ball of mind is rolling: what makes it stop, is it red, blue, green, yellow, shapely smooth or evanescent smoke, luminous, or dark? Is it for always, is it forever. Or is it just temporary, staccato thought-forms making up a story line to follow, to be? We are careful not to interrupt our agony. Our basic nature might actually be space, but that’s not comforting. How about throwing in bliss? OK, but can we still tango? I’ll still hold out for something good to happen, something demonstrably exciting with built-in exit doors. All that space and no place to go, a lived-in-life is not so bad after all.

Which brings us to duality. We are, it seems, of two minds: Mind of space and mind of form. Mind of space is primary, it is said, and form is reflection. Space is reflection of form, also, by allusion. Mind of space and mind of not-space, spars with mind of form and mind of not-form in a mirror dance. One can not take the other out of the line-up. They are interdependent, mutually supportive and intertwined as informs –space as intelligence, and tree or bird as a dimensional demonstration of the information communicated or manifested by the intelligence. Taking a leap to or a swat at the other is futile and only shows a bias for some preferred territory or terrain or Mindscape. Where to fix the mind? Where to reside as mind devoid of existence? We begin to see the Prajnaparamita sutra as the Buddhist Ark of the Covenant. It just swings open the gate to transcendent wisdom-mind. But we never see a protagonist like Harrison Forde risking everything to retrieve a copy of the Heart Sutra, because our idea of what constitutes power is misplaced. The mind of being in-form is deceived by the idea of domination, of taking or having more than the next in-form, and of valuing knowledge over wisdom. In action it acts to protect its projected ideas and interpretations about the form world, especially since primal space can’t be appropriated, only veiled by lies. If you hold genuine diamonds in your hand, there’s no need to toss them away to covet a hand-full of sand. It’s not good economics and it’s not good common sense, but sand is what is being touted and sold in the real world we share. Ninety-nine percent choose sand over diamonds. So the truth or dharma that the Buddha taught, and that is realizable, is indestructible awareness, and the sand that we prefer is a handful of temporary distractions that are the glamours of the mind. Meditation is an antidote to the habit of reaching for the sand. Discriminating awareness sees the actual nature of the genuine, original treasure. Less we devolve at this point into pirate stories or metaphors, we will leave it at that.

The iconography of The Celtic Buddhist Mandala

The underlying structure of the mandala is a sacred geometric form called Metatron’s Cube. On it’s own it may be studied and taken up in contemplation, perhaps valued from a Pythagorean point of view. Metatron’s Cube contains all the platonic solids. I chose this form because it was interesting; it has a valid basis in Western science and thought, in the cosmologies of Western thinkers from Plato to Kepler. Each one of the five platonic solids has been related to a particular element and in combination the elements make up the world we experience. In this way they may be related to each of the five Buddha families and have a place and function in the mandala. As the mandala may begin with a point appearing the center of a sphere so too the drawing of the geometry of Metatron’s cube mimics the natural creative progression of manifestation. Thus, Metatron’s cube is a good form for expressing and conveying the notion of form is emptiness, emptiness is form. Then we find Prajnaparamita, emptiness as the mother of all the Buddhas, in the center of the mandala. She represents this very notion as deity-vast and luminous space. And she is awakened prajna or insight beyond concept. Thus she is looked upon as the secret wisdom dakini. She is four-armed holding a dorje in her right hand, and a red cloth –covered book (the Prajnaparamita Sutra) in her left hand. Her other hands are held up in teaching gesture (Dharmachakra mudra- turning the wheel). She sits on a golden, jeweled, lotus throne held up by eight dragons.

(* Visualization practice) (Prajnapamita and mandala practice)

The mandala reflects some aspect of the Celtic Buddhist lineage and is also personal and transitional. There is some representation of a cosmology. It borrows from the traditional depictions of Buddhas, deities and protectors, such as Samantabhadra/Samantabhadri, Tara, Vajrayogini, Maitreya, Ekajati, and Dorje Trolo.

These archetypes are drawn and painted according to the traditional Tibetan principles concerning proportion, iconometry, motifs, and symbols. My main source is Tibetan Thangka Painting by David and Janice Jackson. And for the Celtic designs, my main sources are: Celtic Art by George Bains, and The Book of Kells.

For instance, in the Celtic Buddha painting one can find a similar motif in the portrait of Christ and the portrait of St. John as portrayed in the Book of Kells. There are other esoteric ideas the paintings that I would rather not spell out. I do try to present an accurate picture of the mythology of mythology of the deities as they have evolved over time and also to bring the deities into a new light or archetypal function that would be available to a tantric path. The whole process of painting is entirely intuitive and as a practice it is quite dynamic, because painting the deity in detail is a visualization practice. It is meditation in action. Various transformations and realizations may come out of the process of drawing and painting - a relationship gets developed. The energy of this whole procedure gets built back into, or gets incorporated into the painting. Thus the archetypes take on a life of their own and may be used as supports for meditation.

Here are some ideas that will show the way the painting is organized. It is set up to indicate the five Buddha families and the enlightened activities of pacifying, enriching, magnetizing, destroying and accommodating. These ideas are taken from my notes on the teachings of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche and Venerable Seonaidh. In a general sense these energies may be worked with on a political, karmic or spiritual level. They may come into play in relationships and environments and so they may be treated and applied as psychological constructs in one’s personal mandala. One of the ways we work with these energies is in their activity to alter situations that have gone far out of balance. For example, in the pacifying mode, we may create harmony where too much disharmony occurs. Internally, there is a purifying action, a more gentle purging and a reduction of the intensity of the afflictive emotions; and externally, our presence exerts a calming influence, one doesn’t enter into the fray. So the Bodhisattva action of that is that energy is redirected so it pacifies a situation. In a spirit of non-engagement we take the energy, feel it and neutralize it.

In the enriching mode, we may clean up the environment and manifest some degree of personal elegance, some degree of well-being. Therefore, there is less clutter. We pay attention to small details in the environment; precious things have their own place in the mandala, their own qualities of energy. When we pick things up, we become aware of their energy rather than just the physical form. We may start to feel some shift in the energy of things, notice the difference between the heat, different groupings of plants or arrangements of sense objects. We might have people over for dinner or go to a concert. We create some new kind of enriching space in our lives. Perhaps there is a sense of fulfillment of potentialities, or possibilities. In sitting meditation, each practice has its own karmic manifestations and there is a gathering of merit. In terms of our bodies, as a Bodhisattva we may be slightly masculine and slightly feminine. Energy comes from a quality of practice; there is a particular glow that one sees in various teachers like Trungpa, the Karmapa, or Kyentse Rinpoche.

In the magnetizing mode, it may be characterized by attractiveness, there is an enchanting and seductive quality. When we magnetize our physical being and environment, dralas or fairies are brought in by that quality. There is a drawing in of the energy, expanding it and sending it out. Internally, obstacles may be overcome; awareness is awakened in the environment and is energetic and transforming.

The destroying activity deals with cutting through our neurotic fixations and others, as well, and being able to say no. Saying no to our habits. Crystallized thought formations are obliterated, on the spot. There is a clear quality of being non-attached, but directed. The energy from non-dual space is available to be used for vanquishing and destroying negative forces.

And in the accommodating mode we make ourselves available without condition. We could actually like ourselves and thus give some emotional acceptance to others. There’s a sense of bravery, of going beyond one’s comfort zone, of extending further without the fear of looking foolish.

When we think of spiritual practice and these complicated setups, we have to remind ourselves that we are healing the psychological problem of not seeing ourselves as spiritual beings. The setup is the mandala, it presents a structure to be worked with and through which we contact our basic makeup.

In the mandala painting these qualities and some of the deities or archetypes that may accompany working with the energies are seen in the four directions and the center. The organization is set up to indicate the five buddha families. Their action is transcendent, helping to transmute negativities. They are hidden in the painting, but inferred by the colored disks in the four directions indicating the presence of the Dhyani Buddhas. They are held to be five constituents of the human personality. There are accurate descriptions and explanations of the five Buddhas in The Tibetan Book of the Dead, In general, the lustful deities are employed to transform desire, the tranquil deities help transform confusion and the terrifying or wrathful looking deities could be evoked to deal with the energy of anger. It could be argued that Bridget, Danu/Anu and Cailleach are aspects of the same Great Goddess. It could be that they are still present as subconscious energies that when connected with have the capacity to enpower or initiate. They, along with Cernunnos and other Celtic archetypes embody the elements and whatever phenomena manifest, like lightning or volcanic activity. There are processes in the body that match the processes of the sun and the moon. On one level Cernunnos or Anu could be a deity who makes us aware of our environment, and our interdependence with the natural world. At the Mahayana level, there might be more celebration, dancing with the deity, walking in the woods. The sun coming out in the morning is the expansion of the deity. There is a joining or union with that whole activity and a joining of masculine and feminine qualities. On a Vajrayana level, you are the deity, united with the form, mantra and wisdom of the deity. Phenomena come to you and communicate with you. The rotation of the seasons could personify as different aspects, we feel young in the springtime and die in the fall. Cernunnos and the other Celtic deities introduce us to the natural world. And in that joining we feel the feminine nurturing quality that’s inherent in the whole process of life.

In the same way, Prajnaparamita, Tara, Vajrayogini, Ekajati and Samantabhadri share similar relationships. While Tara and like deities may be invoked to bring material blessings, grant wishes and healing, as well as remove obstacles to experiencing a better life, they are also proven initiators that can introduce the practitioner to a mystical dimension and understanding of wakefulness and co-emergent Wisdom. They prod the practitioner to dwell in egolessness.

Perhaps we could take a tour of the mandala by imagining ourselves sitting in the center on the lotus throne. The throne rests on a joy swirl in the center of a transparent crystal, or golden Celtic cross. To our front, we are facing east, the characters are seen in a blue light. It is spring-time, the water element is dominant and we are addressing the Vajra Family, which is pacifying or purifying. The presence of Bridget is peaceful and inspiring. She is associated with fire and water, the morning sun and springtime. She holds the red sun in her hands- her name means variously “exalted one” and “bright arrow”. She is standing in the doorway or on a threshold. She has dual roles both as goddess and saint. The harp signifies her connection with the arts, and especially the bards and the poets. The stone vessel and ladle beside her represents her role in healing, in general, and the healing waters of sacred springs. On a deeper level one may discover different qualities associated with Bridget as one explores the archetype. It should be explained that whatever one might experience in meditation need not match the qualities, ornamentation or appearance that this writer, or any other writer has emphasized or described. In the actual meditation a deity may be active or passive, an energetic presence or invisible. This should be left open. So the mandala painting is just a suggestion, a starting point, an approximation.

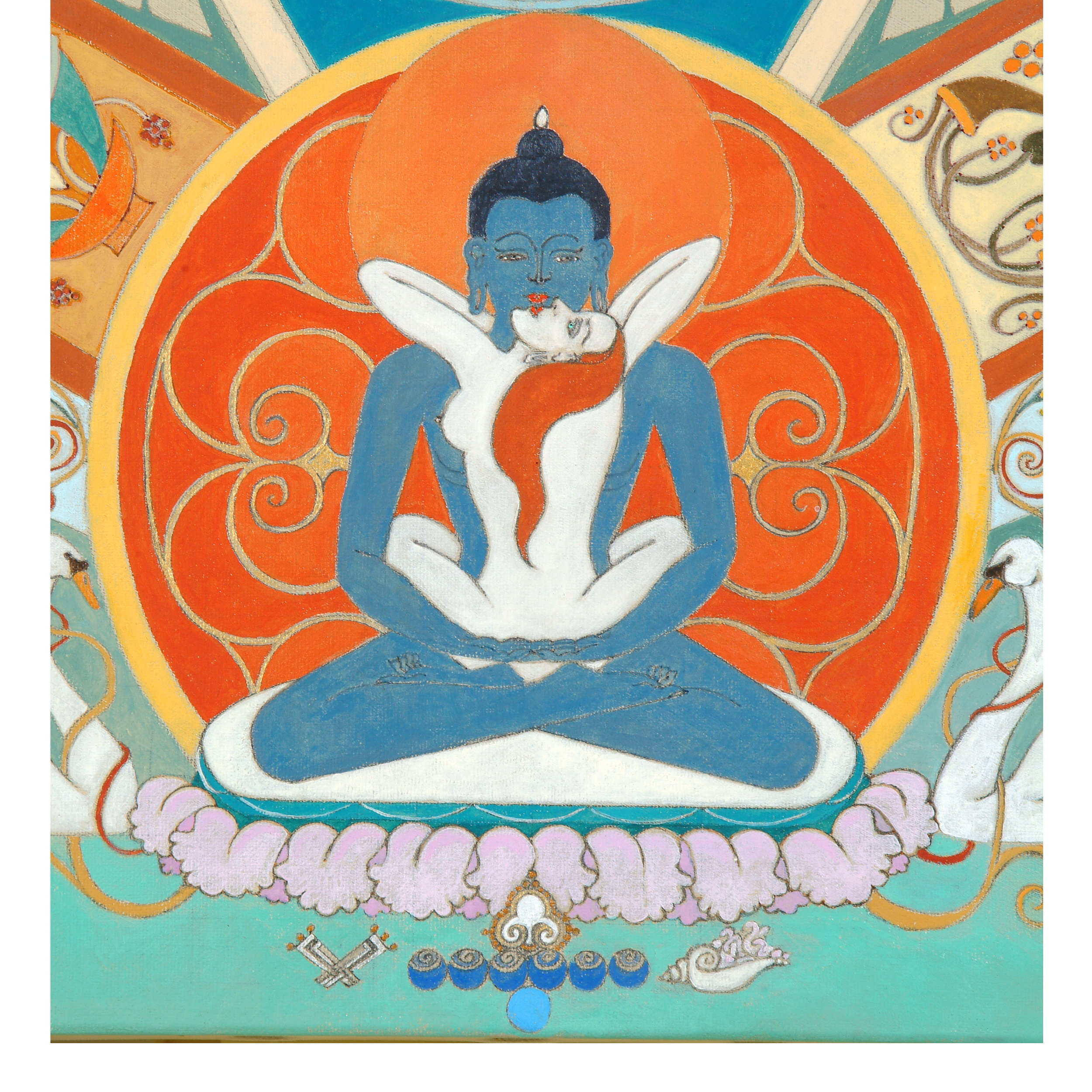

Samantabhadra/Samantabhadri in consort are the unadorned Buddha quality of the primordial space, the original wakefulness beyond concepts. He is dark blue in color representing the dharmakaya; and she is white in color and naked to demonstrate the unadorned nature of Absolute Truth and the emptiness of all phenomena. In the older schools, she is the mother of all the Buddhas. We may place Vajrasattva here, as a pacifying archetype of the collective compassion and purity of all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

Also, in this direction we see the blue Vajra-buddha, Akshobya in consort. The purifying of anger or aggression, that holds potentially the wisdom quality of Mirror-like Wisdom.

In the East, to our right, in a radiant, yellow-golden light, we see Cernunnos, riding on a stag. In his right hand he is holding a golden torc and in his left hand he is holding a ram-horned serpent. Yellow Tara, (Vasundhara) the golden goddess of wealth, bounty or abundance, is seated in the middle on a lotus. We can be receptive to the richness, abundance and generosity of the universe. Then there is Anu or Danu as the mother aspect. She is seated on a green mound of earth, holding the stem of a lotus. One could hear the buzzing of bees, the singing of birds and smell the fragrance of wonderful flowers. In the beginning of summer, Anu and Cernnunos sort of team up and are consorts. Then we have the presence of Ratnasambhava and consort who are the yellow buddhas of the Ratna family bringing enrichment and fulfillment to the spiritual process. Ratnasambhava transmutes human, intellectual and spiritual pride into the Wisdom of Equality.

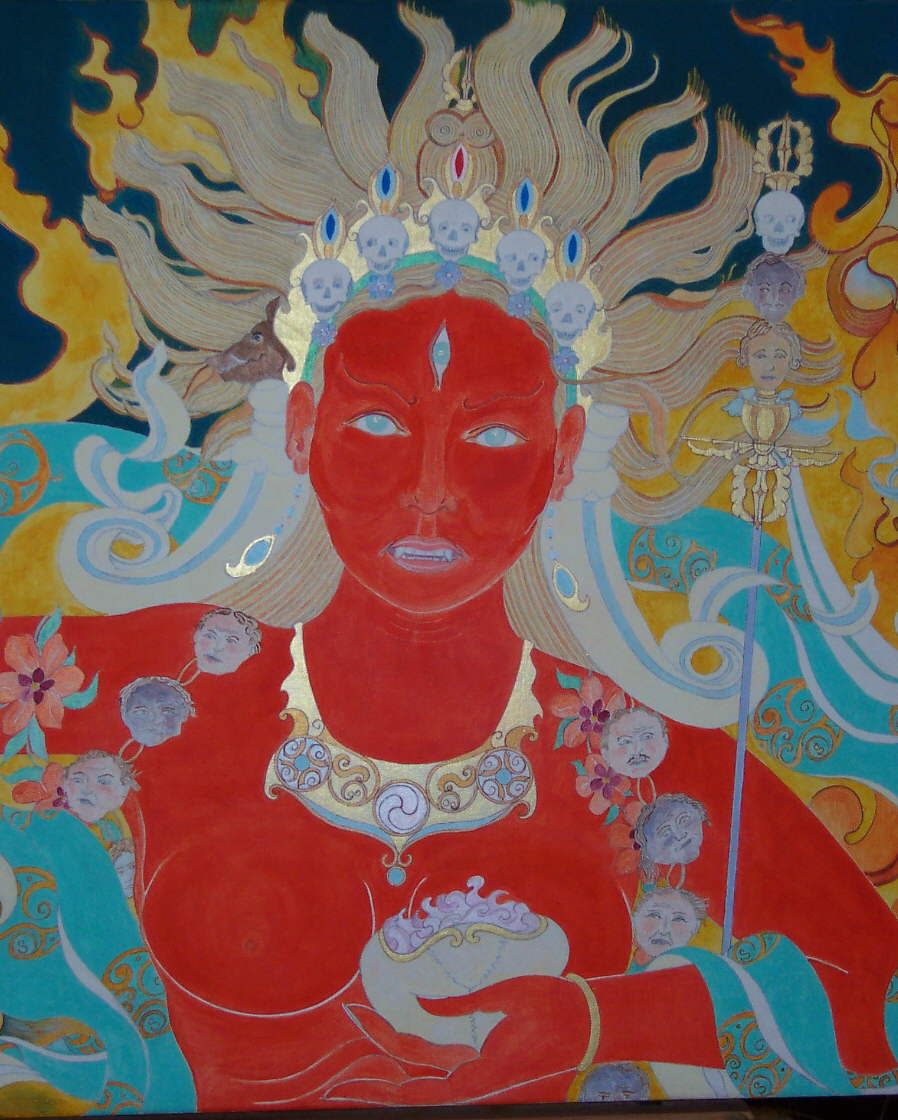

Behind the central deity, in the West, a red light is present. This is the realm of Vajrayogini, the Vajra Dakini. She is red in color, the feminine Buddha and archetype of wakefulness that conquers the ego. She is referred to as the Coemergent Mother. She holds a hooked knife in her right hand, which is symbolic of cutting through neurotic tendencies. In her left hand she holds a skull cup filled with amrita which could be a symbol of wisdom or fanatical beliefs, which make us drunk and whoozy. She is engulfed in flames, which are symbolic of transmuting attachments into compassion. She is magnetizing in appearance and action. (See Vajrayogini thangka)

AnaDaire in consort are seated on a lotus. Avalokiteshvara may be located here along with the Padma family Buddha, Amithaba, red in color, in consort. The Wisdom of Discriminating Awareness.

In the actual painting, our teacher, Venerable Seonaidh is in the upper left-hand corner. He is seated on a chair with a pug at his feet. On the right hand side is the sixteenth Karmapa seated on a throne as he appeared during the Black Hat Ceremony that I attended in Boston, I believe in 1975. Seated on a throne in the upper right-hand corner is Maitreya Buddha.

Continuing around to our left in the mandala , we encounter a luminous, green ray of light in the northern direction, the domain of Amoghasiddhi and consort, of the Karma Buddha family. Ekajati, Cailleach, Dorje Trollo, the owl headed dakini, all wrathful or semiwrathful archetypes that have a destroying quality and help to transmute jealousy into All Accomplishing Wisdom. Green Tara could be placed here, helping to clear obstacles on the path or a fulfillment of ends. But Ekajati, the protectress of mantras, may be seen as a wrathful form of her. Some wrathful deities may help with the cutting through of doubt and hesitation.

Cailleach is blue and is seen riding on a wolf. Cailleach’s reign begins with Halloween or Samhaine. She is also a very ancient Goddess; as a goddess of Sovereignty it was believed she tested the Kings-to-be in the Celtic world.

She was also the protector of deer and wolves. It has been written that she is blue in color, with only one eye in the center of her forehead. She is mother earth in wrathful aspect, in the guise of winter, and in her creative aspect, she is credited with the forming the land of Scotland. In Ireland, many landmarks, peninsulas, hills and sites are named after her.

The Owl-headed dakini arose out of my involvement with the first painting.